Waking up, I turn on the light and find myself in a 45-euro room in a guesthouse that will accept my dog: the landlady is charging five euros extra for the privilege. I don’t receive a reply to my question whether this includes breakfast or not. But bringing pets, she says, is allowed in principle. So I’m using the remote control to consult the comrade on the corner up where the wall and the ceiling of the room meet, to call up the weather forecast. No change in sight. It will remain hot and dry. Fabulous weather for tourists, bad for the forest, for agriculture and the climate. Avocado and orange trees being planted in monocultures around Silves like lifebuoys have no chance to survive this year without artificial irrigation, as it’s not raining. Still, we have the reservoirs right nearby. The idea of using the water more sustainably doesn’t enter the head of any functionary working in the agriculture and environmental bodies of the Algarve.

So how much time do we have left in truth? How large is the hole in the side of our ship? When will it sink? Let’s take this time for ourselves – at the same moment when representatives from 195 states of this world meet for the 26th time for an international climate conference called COP, this time in Glasgow, to prepare the most important decision for humanity, in the words of the journalists in the capital…

Back to Nature

No, I didn’t fly to Glasgow to report from there. Instead I connect with nature by crossing the bridge of the 124 national road at Enxerim and turning left straightaway into a country lane. The time is just before nine in the morning. And it’s so easy to be swallowed up by nature, to be away from the tar, concrete and modern architecture as well as the traffic noise. Uncultivated fields and abandoned houses line the old pilgrimage trail. You can’t really picture that just driving by in a car. At some point there are no longer even any ruins left. This is a different way I have decided upon: going on foot means to see more, to hear, smell and feel more, too – all senses are awakened in the process. Also, you get to look behind the scenes of a country. Following the red and white markings I reach a narrow pass leading directly east, accompanied for a long time by the dried-up bed of a brook littered by the remains of felled eucalyptus trees, simply left lying there.

Personally I took a completely different decision this year, is how I sum it up for myself on my way on foot cross country, writing part of this story in my hiking diary. Yes, it’s way too hot for October. We won’t need to hold a climate congress to discuss the issue. Yes, we don’t have enough rain in the autumn and winter. That too needs no more discussions. At the same time a few foresters and the Navigator Company are planting ever more monocultures stealing the last water reserves from the soils and destroying biodiversity. This is one of the many issues we should pay attention to: what do we do with our water in the Algarve and how do we save the biodiversity of our local fauna and flora? Shouldn’t we all slowly start to put our money where our mouth is, seal what we know to be the hole in the ship’s wall, or, phrasing the question differently, only plant native tree species that suit the water supply system of the region, thus reducing the risks of forest fires? Should we stop for a moment and ask ourselves whether it isn’t true that you can’t eat money, and whether it’s not a lot more important to use water sustainably?

Flying to Glasgow, emitting even more CO2 in the process and losing time with speeches instead of making clear international, national and regional decisions on the ground? No? Everyone knows what this is about: to end the industrial supremacy over nature. This weaning off process is definitely not an easy cure. But the fact that money may only be earned in harmony with the laws of nature has to slowly dawn on any local politician and entrepreneur. For how long do you want to keep placing the laws of the market economy above the natural laws? If so, for how long does humanity want to carry on subjugating the Earth, instead of integrating itself? And if the community of 195 states is still unable to come to a decision on a concrete climate agreement because it just wants to carry on as if the current situation was just fine, or if they end up paying only lip service to the need for change, then natural disasters will reduce the numbers of humanity on planet Earth. The water of the springs, brooks and streams is drying up and we are looking on as the summers are getting ever longer and the winters ever shorter. Rains have been diminishing for many years now. Inland ground water levels are sinking. Climate refugees from drought regions are streaming into Europe. At the same time there’ll shortly be ten billion of us, using water as if there was plenty left, and at least eight billion of those are continuing to burn coal, gas and petroleum derivatives on a daily basis, for cooking, producing energy, for driving and flying; for our general comfort. It’s getting warmer, and in a few years we’ll already have reached those 1.5 degrees Celsius mentioned in the Paris Agreement. And then? Will we go down dancing and singing, like the passengers on the Titanic back in the day, no matter the size of the hole in the vessel wall?

Is Less More?

The consequences of climate change are already hurting today. I think we journalists shouldn’t be afraid to touch on these sore points, when rivers burst their banks and dykes break, or vice versa, when droughts put life on our planet into question, when the water dwindles and nothing is in balance anymore. As journalists it’s up to us to describe the background and contexts without restraint. The planet is slowly starting to defend itself, becoming uninhabitable here and there. At the moment, the damages are still masked by subsidies and insurance policies. How many years in a row do we allow the drought to dry up brooks and decimate biodiversity – or thunderstorms to bring dried-up brooks and streams to overflowing through hail and torrential downpours until there’s no more money left for reconstruction? It would be simpler to take to heart three words: less is more. Don’t get me wrong now. There are ever more of us humans living on this rather limited planet, and most of us are living their daily lives as if it was the last day at the casino, as if there was no future left for the next generations.

So it’s politics that should find ways out of the crisis, greed and excess? Those co-responsible for climate change who every day turn the key in the ignition of their car should know what they are doing to humanity. They should know that their engines burn petrol, the exhaust emitting CO2 and many other toxins into the atmosphere, smelly stuff that is attacking me on my hike. Are we, humanity, taking ourselves too seriously, while not even taking the climate change we initiated seriously?

In my capacity as a journalist I won’t fly out to whatever climate convention as I did in the past, including Glasgow, won’t participate in meetings where there’s a lot of me-me-me talk, more talk and yet more talk, conventions where everybody is just thinking of themselves rather than the big picture. Everyone knows that we’re now scraping the barrel. Which is why I no longer fly anywhere. And I’d recommend to anyone who is in a position of power to start by calculating their own footprint and go on to renounce things themselves, or at least to take a first step towards climate neutrality and to take to heart the motto: less is more. Taking the train to your destination can be a beautiful thing. Or simply hike for a few days rather than choosing a holiday destination you need to take the plane to …

So what’s our attitude to commitment?

My CO2 footprint can no longer bear flights or rounds of talks leading nowhere in the end. I’d rather stay at home, looking after our young cooperative forest and prepare something aiming to support the resilience of forests. Together with my friends I’m installing a sprinkler system to ward off potential forest fires in the future. A piece of good news reaches me on my second hiking day: our ECO123 crowdfunding drive has managed to secure the financing of the sprinkler system. We want to plant a diverse forest, to reduce our own CO2 footprints amongst other things and to show that biodiversity can serve the needs of everybody.

There are things I myself have been practicing for years: I no longer fly, no longer eat meat, sausages and other derivatives of dead animals. It’s not easy to learn to renounce these things. I’ve now bestirred myself to undertake this long hike to explore the state of my own world. Over a long period I’ve managed to reduce my needs, reducing my annual footprint to around one ton of CO2. Compare this to five tons CO2 emissions for the average Portuguese person and eleven tons CO2 for a German. My goal is to reach my own climate neutrality as quickly as possible: preferably still in 2025. How am I going to achieve this? For the past ten years already I’ve been producing my own power and the electricity I need for my workspace autonomously, using 40 solar panels which produce 14,000 kWh every year. My own consumption of green power is produced by myself, and the feeling that I’m able to change something for the better is a good one, at all levels. Responsibility for this lies with me and not with any government onto which we can always shift the blame for everything bad. Every year I add a small CO2 reduction. And my footprint in terms of mobility and domestic use is going down. We mustn’t just criticise politics for its lethargy, but rather have to start tackling climate goals within ourselves, including doing away with certain things and changing our consumption patterns. Of course we need the political framework, but on its own it’s simply not enough.

Let’s stay completely with ourselves for the moment. Every one of us is part of a system and everyone has overheated this system by burning coal, gas and oil to the point where we will be presented with the bill for it till kingdom come if we don’t advance in the right direction now. We humans have unsettled the balance of our life in nature, but we could still stabilise it again by living more mindfully, following our principles more strictly. This however is hard work and requires a different understanding of life. This is something politicians should communicate and no longer embellish the way to climate neutrality. This requires renouncing certain comforts, while advancing human values. Instead of living our lives guided by rivalry we’d need to „only“ cooperate in a fundamental way and to summon respect for all other living beings that we should no longer torment in industrial livestock farming, slaughter and eat. This would be a first step in the right direction, eating less meat and …

… consume less energy, which also means wasting less energy, to handle less energy, to take things down a notch. Let’s turn off the light on our planet when we go to bed. Let’s slow down, go to bed and get some rest when we’ve done enough to get by on, whether in 40 or only 20 hours a week. Let’s become more frugal. Let’s help others, let’s share our wealth with all other inhabitants of this planet. Have we still not grasped that we enter this world naked and leave this world again naked? We can’t take anything with us of material value. We could however leave behind something good on this earth, an atmosphere in balance and in peace. Each of us can do that. This thought is always on my mind, as long as I may still journey on foot. Which is why it’s a good idea to step off the accelerator and learn again how to walk on your own two feet. The emissions problem is solved by a kind of mobility which includes going on foot – instead of flying away on holiday, driving to work, to the shops around the corner, or the club. And I always notice when my own forces are diminishing. That too is important, to get to know yourself and your limits …

Walking is humankind’s most natural way of locomotion. I realise that for myself when I head off on the second day of hiking from Silves, after an excellent breakfast with a lot of fresh fruit, on my way to S.B. Messines, the next stage of my hike eastwards. I’ve topped up my water bottles. My first stop is the mysterious Funcho reservoir lake.

We enter the year 2022 when the profession of forester or ranger no longer exists. The profession became extinct towards the end of the last century in Portugal. There is a small „troop of stragglers“ part of the „GNR Ambiente“, with its seat in Portimão, note that we’re talking about seated and not patrolling; the entire southern region has seven police staff on the state payroll. Only two per cent of the forested area of Portugal are owned by the state. So why should the state fork out if it doesn’t even own the forest? This is another way to shirk responsibility and to leave conservation to private forest owners. Well, the result can be seen vey clearly on the way from Silves to Messines. No, I’m not walking on the EN 124, which once outside of Silves no longer features a sidewalk, despite the excess speed of the drivers. I take the country lane running parallel to the EN 214, the Via Algarviana, an official long-distance trail in Sector 9, where no significant investment has taken place for many years, and which gradually moves away from the EN 124. At some point I can no longer hear the road traffic.

What are the benefits of a long-distance trail to the Algarve and its communities? The answer is two-fold. As in the short term it surely only creates costs, money has to be made in a different way, which is why there the forest is regularly turned into money. Only recently, in summer, the last trees are felled, the branches cut and simply left on the path, like trash, as the leaves are of no real use to the Navigator Company and its industrial complex, nor to the local forest owners. Thinking about it – the entire material of the trees – could be transformed into electricity if it was shredded and composted, as biomass. Here in particular, legal regulation would be a great idea, as this rubbish left in the forest is highly flammable and often sparks disastrous forest fires. And it would mean to use resources wisely. Not all lumberjacks understand this logic. They don’t understand (yet) what sustainability means.

The Eucalyptus System

It always starts by contacting a team of lumberjacks (madeireiros) with motor saws, and negotiating a daily fee. A 30 to 40 ton truck with a crane is hired for loading and removal, which takes the result of the daily work of the lumberjacks to the factory in Setúbal or Huelva for processing. At the end of the process the consumer receives pristine white chemically bleached paper that the manufacturer puts forward for export, ready to go. Today’s modern work life plays out in the office, and these offices still need the paper of Portugal. And everybody is taking part in this business, a business that is too linear and envisaged along lines that are too short-term. The private forest owner providing the land receives a premium of at least 500 euros, cash in hand. In Monchique, the Navigator company is promoting this direct subsidy through A5 flyers. The Brazilian lumberjacks often hired for the job are doing the dirty work in the forest. The state turns a blind eyes. Presumably it doesn’t matter whether a lumberjack is registered or not, as the paper industry is a faithful taxpayer, one of the few that by doing this also generate political power through lobbyism. Laws from Brussels are creatively sidestepped, at best ignored. There is indeed an ICNF*, which for many years hasn’t seen the forest for the trees, yet wants to be responsible for conservation and compliance with its laws. For that particular body, eucalyptus is just one of many species of trees that were introduced for the first time in the mid-19th century in Portugal and is by now classified nearly as a native tree species. It’s high time that the ICNF is finally made to take responsibility for its policies. Maybe it might just emerge which value laissez-faire has in conservation, how many contacts are required. In any case, the letter „C“ in ICNF may also be interpreted as standing for „comercialização” instead of “conservação”…

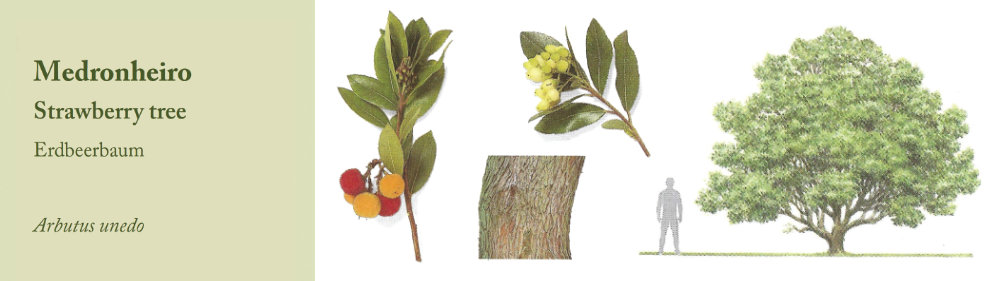

It’s been three hours now, it’s midday already when Max and find ourselves struggling along a path supposed to take us to the Funcho reservoir, in an area where all we come across is dried-out springs, empty brook beds and felled eucalyptus. Despite everything we are treated to wonderful tourist weather. No people, and most of all, no animals, to be seen anywhere. Back in the day there were at least snakes sunning themselves and fish in the brooks. Extinction, I am imagining right now, started in just such a dried-up biotope near Silves that even humans can hardly withstand: there’s no shade anywhere. No tree with roots to hold the soil together. Max and I are put to a tough test here, walking in the full force of the sun. Should we risk taking a break in the glaring sun and dehydrate even more? No water, anywhere. All hills are bare, the soil the colour of sand. Above our heads, six power lines carrying 300,000 volt. You can hear their humming and hissing. The path is lined by medronheiro bushes that have long adapted to the dry conditions. From 12 noon onwards our water supplies too are dwindling. The powers of nature, the sun and wind, keep drying out the eroded soil of the hills to the east and north of Silves, blowing the dust through the valleys and across the hills into nirvana. A death zone for hikers with insufficient training and not enough water in their backpacks.

In the summer of 2003, the forest around Silves was ablaze for an entire month, and since that mega fire there has been no reforestation with cork oaks or umbrella pines, no rest for nature. Reforestation? Only in the private interest, and then exclusively with eucalyptus and in the shape of monocultures. This is the exploitation of nature at its most brazen. The land reminds me of images taken by Sebastião Salgado in the goldmines of Africa or Brazil. It is here that the steppification of the Algarve through climate change will begin, if the footpath, along the Via Algarviana for instance, is not pretty soon planted with sustainable greenery. In the mid to long term any investment pushing back the desert in the south of Europe would mean a lasting benefit for the land. Land that is abandoned, for whatever reason, is lost to humanity, and lost for ever. Renaturing a desert will always be an expensive pass-time, until at some point renaturing becomes unaffordable. I look around. No settlement, no house, no sign of life. I walk without hurry. Breathe in, breathe out. Slowly I feel my brain too drying out, with every breath I take.

The Idea

Walking. Slowly chewing an almond, eating a dried fig and an apple. Downloading the taste as it were. Thinking of something beautiful. Taking my hat off and donning it again. Shaking the backpack and tying the straps tight again. The last water remains in the bottle, the last-resort supplies. I am worried about my dog. He’s not had anything to drink for an hour, and the last water in my bottle is reserved for him. He’s now always waiting under a bush until I catch up with him. The two of us are as one. He knows that he has to be strong now and use his remaining forces carefully, as I won’t be able to carry him. With his weight of 44 kg we’d simply lie down on the trail and wither. There is no emergency button on this stretch. Nobody will pass by and nobody else is journeying this way. No-one is coming towards us. If any of us were to collapse we couldn’t even call for help. Most of the time, mobile phones don’t work here, most valleys in this area to the east of Silves have no coverage. I send a message to my partner and write a text giving my exact location and that we’re still four kilometres from the dam. It’s only at the fifth attempt that the phone finds a signal and sends the message. Another hour’s hiking. An unimagined loneliness, an unimagined silence. And right inside this image a sound spoils the idyll. A quad bike zooms past us, the couple wave and disappear as fast as they came up to us. One consolation is that things can only get better. And for things to get better, everyone would have to pull themselves together, and everybody would have to take a leap of faith. I carry on walking for another two, three hours and nothing changes. My dog’s physical condition is giving me serious cause for concern.

Rosa Cristina Gonçalves da Palma is the new as well as the former mayor of Silves, having been reelected at the local elections of 26 September, with 6,457 votes. Just over 43 % of the votes cast went to her. Should she find it in herself to reserve in her budget for 2022 and 2023 a few thousand euro – a four-digit amount – and use those funds for afforestation, the old pilgrim path would benefit immensely. One should simply invite the mayor to join us on a hike like this and explain the idea to her in practice. If you were to plant autochthonous trees during the winter months, every five metres just to the left and right of the trail you’d be engaging in sustainable investment in your own region. A school class, the Silves fire service, a dozen volunteers could take on the reforestation along the way of the Via Algarviana and at a later stage the care and irrigation of the trees in summer. Hikers would give thanks for this Green Belt and pay a visitor’s tax when overnighting in Silves to compensate this investment. This would be a long-term investment in nature, in nature tourism, and would push back the steppification and desertification of the Algarve.

No investment, no profit…

And if at the end the budget should yield a few hundred euros more, you could set up two benches and a table for hikers on a hill with a 360-degree view, so they may sit down during a break from hiking, eat a sandwich and take a sip of water. No need to install a Coca-Cola dispensing machine in the middle of nowhere… But shade is of the essence. And best provided by trees of course…

Atop the hill with the best view I look back towards Monchique, from where I started out the day before. At an altitude of around 250 metres we’ve reached a fork in the path. Dog and master take a right and start descending, 180 metres over a distance of two kilometres down into a broad dry riverbed serving as an overflow basin for the Funcho dam. All of a sudden, my dog is gone. I spot him in a brook, wallowing in the water. Happily he looks at me as if to say: look what I found! The hairpin-bend trail hosts only cork oaks, a few holm oaks and a handful of carob trees, slow-growing, frugal native old trees. A spring releasing water dripping from the mountain flows into a brook, which in turn crosses the trail before cascading down into the valley to the right of the trail. What a lucky coincidence. Somebody must have simply forgotten to cover the last corner of Silves with monocultures. I fill our bottles at the spring and take a sample sip. Well, I’ll just have to rely on my sense of taste here. To come across clean water in October here in the Algarve, after a long and hot summer, is the mental highlight of any hiking day. When I undertook this long-distance trail for the first time, just under 20 years ago, there were plenty such springs in the autumn. Today though I’d not been expecting anything, which turns me into the happiest of people right now. Water!

Atop the hill with the best view I look back towards Monchique, from where I started out the day before. At an altitude of around 250 metres we’ve reached a fork in the path. Dog and master take a right and start descending, 180 metres over a distance of two kilometres down into a broad dry riverbed serving as an overflow basin for the Funcho dam. All of a sudden, my dog is gone. I spot him in a brook, wallowing in the water. Happily he looks at me as if to say: look what I found! The hairpin-bend trail hosts only cork oaks, a few holm oaks and a handful of carob trees, slow-growing, frugal native old trees. A spring releasing water dripping from the mountain flows into a brook, which in turn crosses the trail before cascading down into the valley to the right of the trail. What a lucky coincidence. Somebody must have simply forgotten to cover the last corner of Silves with monocultures. I fill our bottles at the spring and take a sample sip. Well, I’ll just have to rely on my sense of taste here. To come across clean water in October here in the Algarve, after a long and hot summer, is the mental highlight of any hiking day. When I undertook this long-distance trail for the first time, just under 20 years ago, there were plenty such springs in the autumn. Today though I’d not been expecting anything, which turns me into the happiest of people right now. Water!

As citizen-consumers we can hardly imagine what it means to have no water left and to be suffering with a hellish thirst. As long as there is a constant supply we can’t imagine either that we might open the tap in the kitchen and no water comes out. People living in towns and cities wouldn’t think about grasping the scarcity of water in a logical way. They are so far removed from nature…

It’s another two kilometres to the reservoir lake. We’ll need a good half hour still before we can gaze into the crystal-clear waters of the Funcho reservoir lake, which prevents the Algarve, in the summer months in particular, from drying out completely. We are traipsing up the trail reaching the stone reservoir wall, 50 metres high, and going along the 100 metre long wall we arrive at a picnic area in the shade of fine old umbrella pines. It’s 2pm. This is it for today, and I think I’d better send my dog home with this October heat reaching 32 degrees Celsius in the shade. Along the past 17 km we’ve found a grand total of one spring. Max will do better to get some rest.

For now we receive a welcome visit by Stefanie, who has organised a picnic in the Parque de Merendas, near the breeding station for the Iberian Lynx. And then? It’s still nearly 15 km to S.B. Messines and its Casa do Povo, the next accommodation stop. From there the plan is to head into the Serra da Caldeirão via Alte and Salir. I decide to head east on my own now.

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia