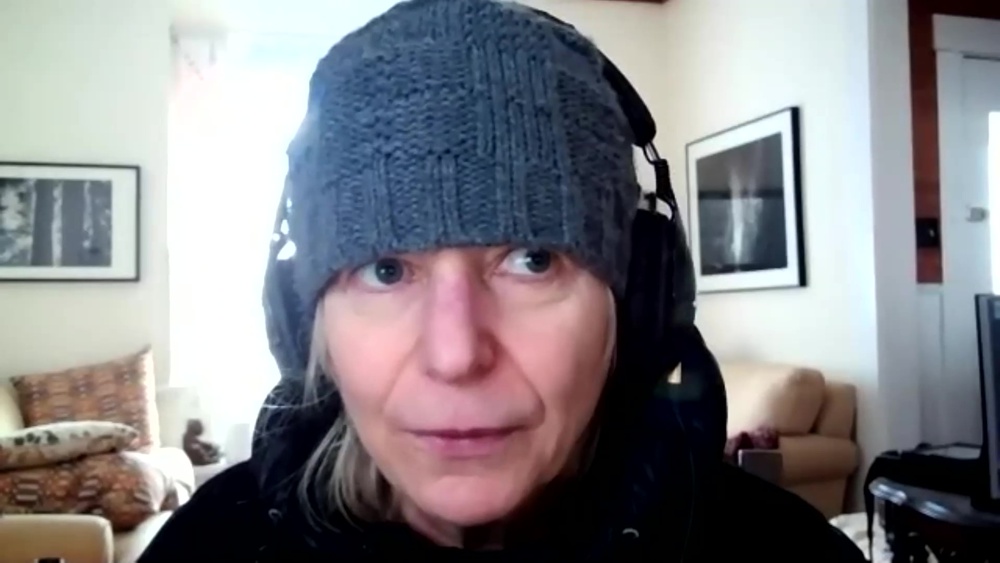

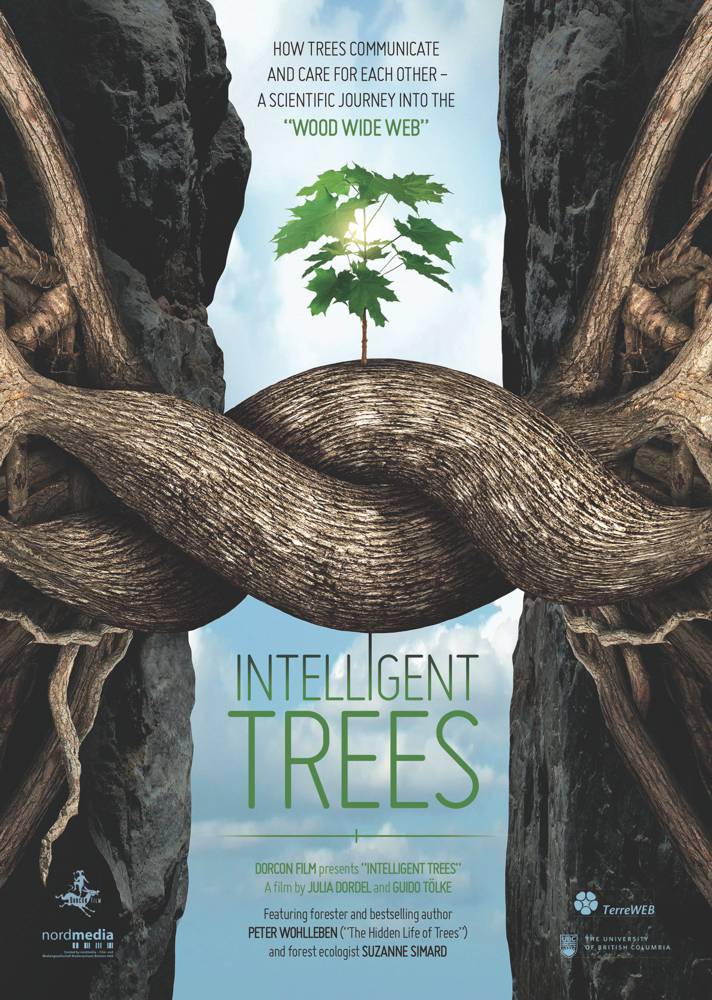

Dr Suzanne Simard is a professor of forest ecology teaching at the University of British Columbia in Canada whose work focuses on how trees communicate with other trees. The passionate educator and TedTalk speaker was given an exclusive platform in the film “Intelligent Trees” to tell the most interesting eco story of the year. Dr Simard used radioactive carbon to measure the flow and sharing of carbon between individual trees and species. She discovered that birch and Douglas fir share carbon. Birch trees receive extra carbon from Douglas firs when the birch trees lose their leaves, and birch trees supply carbon to Douglas fir trees that are in the shade. Currently working out of a small town in eastern British Columbia, Dr Simard, who has a new book coming out in spring, is part of an ecosystem of international researchers and forest fans including the forester and best-selling author Peter Wohlleben in Germany (The Hidden Life of Trees, 2016) and the maverick ‘walker-writer’ Robert MacFarlane (Underland, 2019) in the UK. ECO123 spoke with Suzanne Simard on ZOOM.

An interview by Kathleen Becker and Uwe Heitkamp

ECO123: When we plant a tree, we know that it will be compensating for CO2 – between ten and fifteen kilos in its first year. Do you know how many tons of CO2 make up your own footprint per year?

Suzanne Simard: What my carbon footprint is? It depends on the year [laughs]. Right now, my footprint is really small, because I’m at home during Covid, and not travelling. Sorry, I don’t know the answer to that question, I’ve never thought about it.

You are a biologist as well as a forester. Do you have favourite trees?

You are a biologist as well as a forester. Do you have favourite trees?

In British Columbia, there are 50 tree species, it’s hard to pick out your favourite, and it has varied over the course of my life. But the tree I have studied the most is the Douglas Fir, a false fir actually, which has a wide distribution in the western part of North America, and, because it’s dotted around our town where we live, it’s one of my favourites. But the other species I really love is our subalpine fir, which is a true fir, and I feel a real kinship with them because I spend a lot of my free time up in the high-elevation forests skiing amongst these trees.

Here in Portugal, forest fires are a constant threat. If you owned one acre of burnt forest, what kind of trees would you reforest it with?

It would depend on where I was. I live in a mountainous province, and the one species that is easy to establish after fire is pine. We have lots of lodgepole pine around here. But any of the six species of pines in British Columbia would be fine: they come in quickly after fire; they associate with the mycorrhizal fungi, which are really prolific after fire; they join together and they seed in very rapidly. So, they heal the web really quickly.

So, when you open your door, how far are you from the forest?

My little town in the Selkirk mountains has only got 16,000 people, but I’d say there’s about 15 species of trees. When I step outside my door, I walk about ten minutes and I’m in the forest. I walk up my street or across the lake to another forest. They’re very different. In my own back yard, I have a beautiful maple tree, and a whole bunch of western red cedars, also very beautiful. It’s like a Food Forest. I also have a garden where I grow all kinds of squashes and corn and tomatoes…

You have a book coming out, Finding the Mother Tree. How do you actually find them?

You know, when I was mapping this web of connections below ground – these fungal or mycorrhizal connections that link all the trees of a forest together – we realised that the biggest and oldest trees were the ones most closely connected to all the other trees in the forest. So, we started doing a number of experiments with these big old trees and realised that, when we plant seedlings around them and allow them to connect into the networks of these old trees, or if we trace the naturally-germinating seeds around these old trees, linking into their mycorrhizal networks really improves their survival and growth. Many experiments later, we realised that they were playing a big role in nurturing the seedlings. So, Mother Trees are these big old trees that have this ‘mothering’ role in the ecosystem.

It’s a very powerful image, isn’t it? As is this image of the ‘Wood Wide Web’, because it links our current technologies to the forest and nature. That must work very well for you in your educational projects?

Yeah, I mean, we all use the Internet. And it’s cool because right around the time when the World Wide Web and the Internet was being invented, in 1989, the early 1990s – I still remember the first time I used the World Wide Web… – ‘Nature’ magazine coined the term ‘Wood Wide Web’ for what I was observing in my forest. I was doing my experiments with trees, looking at how connected they were and how they transmitted carbon and water and nutrients. Becoming aware of networks and how they worked, not just in our built systems and engineered systems, but also in our forest systems, we were starting to realise scientifically that these things were all linked together. And they had such similar patterns. People looking at systems or studying networks, the Internet or social networks, or the Wood Wide Web, use an analytical process, or technique, called ‘graph theory’. Graph theory allows you to analyse the structure of these systems, their linkages and nodes. Certain universal patterns appear, and these patterns are the same, regardless of the kind of system you’re looking at.

In the educational work in the botanical garden we set up by our house, planting native trees, we found that some 96% of youngsters aged between 12 and 18 have no idea about tree species. They know everything about the Internet, Facebook, Instagram, but only 4% of young people between the ages of 12 and 18 are able to identify ten different tree species. What do you think would be needed to improve knowledge about nature in general, about flora and fauna, and about how a biodiverse system works?

Well, you know, the best way to understand and appreciate and love the forest and observe things is to be out in it. You can read about forests, you can watch them on TV, or on the Internet, but you can’t get that personal heartfelt conviction to understand and know the forest until you’re out there. I take my students into the forest all the time, show them things, and they absorb it like a sponge and learn very quickly. So, if they’re able to get into the forest, even just as friends and just go and experience it. They don’t even have to really know what the name of the species is, if they can just learn to appreciate that living being, that individual tree or group of trees, they’ll start to learn right away. If they don’t have this opportunity or if they’re so enamoured with their iPhone or the Internet, people are developing tools and applications that can guide them through how to look at the forest. We’ve developed that kind of technology in our forests in western Canada near Vancouver, programmes that people can use to go on a treasure hunt, like Geocaching. This hybrid model of being in the forest along with their phone or some application allows them to use things they know and love. That can be highly effective. Here in Canada, there has been a big effort in schools to re-indigenise learning, trying to teach students the rooted aboriginal way of seeing the forest. Taking them into the forest, having Elders, for example to guide them through games and exercises. And even if you live in the middle of a city, like Lisbon, for example, there might be parks, or boulevards with some trees. Or, even if you’re just looking at a potted plant, you can get to know plants and trees that way.

We do have a massive forest park in Lisbon called Monsanto, it’s amazing. Canada is a huge country, the second biggest on earth. As a Canadian, how would you say Canadians look at forests?

Well, although I was born in British Columbia, I’m actually French-Canadian. My family came from France, moved to Quebec and then across Canada, settling in the mountains near where I live right now. I do know from visiting Quebec that people are very connected to the forest there. There is a long history of the Quebecois tapping the maple for syrup in the fall, and people do live intermittently in the forest. Even if you visit Montreal, the biggest city in Quebec, there are trees all around. It’s an arboreal city. Alongside strong cultural traditions of tapping for sugars, there’s a strong forestry tradition too, of harvesting trees and managing forests. The forest industry in Canada really started to take off in the mid-nineteen hundreds, and it’s moved from these small operations, of just families managing forests, just like my family did, to more industrial-scale clear-cutting.

You mentioned the Elders. Are the First Nation involved in forest conservation?

You mentioned the Elders. Are the First Nation involved in forest conservation?

I would say that, of the English and French-speaking Canadians, 80 per cent of people live in the cities, and 20 per cent in rural areas. But, in the indigenous communities, the First Nations, it’s the opposite: most live in the forest. And so, their way of life, their traditions, they’ve evolved with the forest and depended on the forest. All of their resources are tied to the health of the forest.

Those who love the forest because they grew up as children very close to forests must feel sometimes, walking through the forest, that we have lost our connection, we have lost our orientation. Now… should we go back to the point where we got lost to find the right way, or should we go on? And we’re not talking about using GPS or a compass here. It’s a deeper question. What do you think? Should we go forward or should we go back?

As you know, we’re facing huge environmental crises of climate challenges, biodiversity loss, water shortages; climate change is going to make these things worse, and so we have to make some huge personal political policy decisions globally. I think our way of seeing the forest is part of the problem. Western science has kind of divorced the person from the forest, people from their nature, giving the idea that we’re separate, and I think this has been a big mistake [laughs]. This is part of the problem: if you don’t understand your environment, you don’t look after it. I believe, basically, because we all evolved from trees and mycorrhizas and the primordial soup at some point, that we all have this innate genetic understanding of what it means to be connected to the earth, that we have just lost our way a little bit somehow. Globally, I think it’s crucial that we get people back into the forest, the natural environment, so that they can learn to love it and make proper decisions for looking after it, and support our governments in policies that might be difficult at first, but are essential. For example, decarbonising our energy sector. It’s hard to do this as an individual, locked in a high-carbon infrastructure.

But isn’t it easy? If we say we want to emit less CO2 we plant more trees. Not just monocultures, but diverse forests. In doing so, I lower my carbon footprint. Full stop. That’s one solution.

No amount of tree-planting will save us from our fossil-fuel consumption. This doesn’t mean that tree-planting or restoring our forests isn’t an important part of the equation! If we can get our forests back to the abundance and health they had a century ago, they can suck up about a third of the carbon dioxide that we’ve emitted into the atmosphere. But that’s only a third, what about the other two thirds?

One third is food: less meat, less fish. Another third is mobility and electricity: how we produce and use it. And that’s the reason we need to know our footprint. Coming back to the beginning of this conversation, we need to know how much we emit… Because, when we say zero emission by 2050, we want to know where we are now. And, if we know our footprint, then we can lower it, step by step.

… We wanted to ask you about your political influence – do you have the ear of the prime minister? Also, the business sector, the logging people, have they tried to co-opt you onto their bandwagon, for greenwashing, ‘Forest Certified by Dr Suzanne Simard’, something like that?

You think I’m far more important than I am [laughs]. I’ve never had a conversation with Justin Trudeau, not yet. I think his intentions have been good to try and decarbonise and to reduce our global CO2 footprint, but he’s also caused delay, and pandered to the fossil-fuel industry too much. He’s talked about planting a trillion trees, which is good. It has to be done very carefully, it could have a negative impact if we don’t pay attention to the land and which species belong where, or don’t look after these trees. As far as the industry goes, they’ve tried to ignore me as much as possible, but they’re coming along now because they have to. I’ve got this big project called the ‘Mother Tree Project’, collaborating with both major and small companies on this big experiment where we are trying to protect Mother Trees in different ways and then see how the forest will recover from different disturbances. And they’ve all eagerly come on board because they know the way they’ve done things in the past is not sustainable.

Thank you very much for this conversation.

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia