Saturday the 21st september 2024.

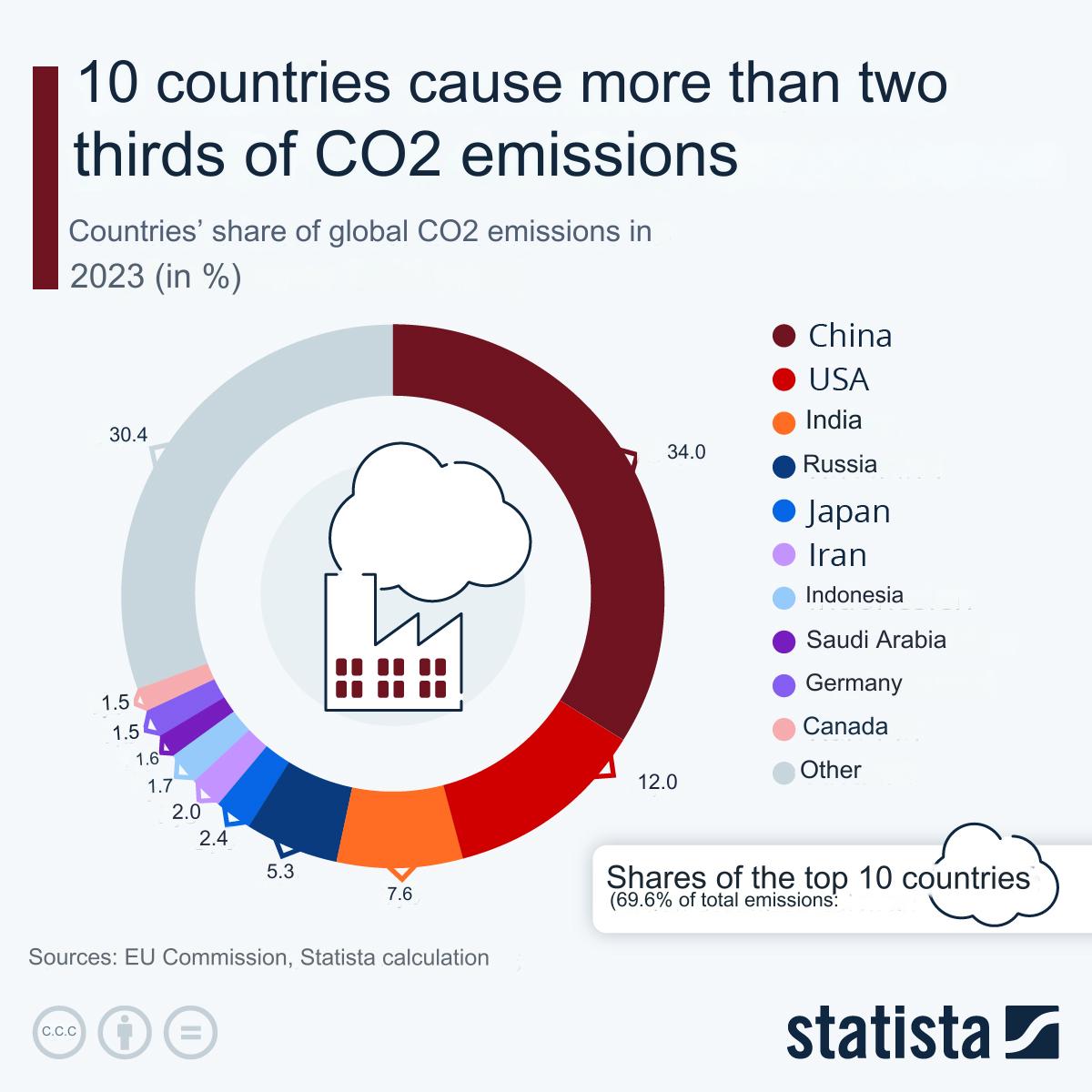

Thinking about our individual carbon footprint can be an important part of the solution to the environmental threats that we face. Of course, we also need to talk about the big climate criminals and find a transnational exit strategy for them: for BP, Shell and Exxon, for Gazprom, Aramco, China-Coal and Rio Tinto, and for the other 93 multinationals that do their business and make their money with fossil fuels and the extraction of minerals at the expense of humankind, at the expense of the habitability of our blue planet. These 100 multinationals emit 80% of the world’s CO2. And we should also take a very close look at the State and its subsidies and tax policies and scrutinise its actions carefully. Why, for example, is one single company allowed to plant ten per cent of the country’s land with highly inflammable eucalyptus? Simply because it is a good taxpayer? Because the forest is nothing more than a simple provider of resources? Everything must be scrutinised. Including my own individual CO2 footprint, of course. After all, I should start by cleaning up my own backyard. Where I can take responsibility for myself, for I’m not just saying that others should start reducing their CO2 emissions. Such a statement also requires me to be transparent.

I bought a plot of land the size of a hectare (10,000 m²) at a friendly price from an old friend who told me that I absolutely needed to buy a plot of land if I wanted to stay in Portugal. That was back in the 1990s. With this piece of land that I own today, it is a little easier for me to consider the question of my own net zero emissions. If you don’t own such a plot of land, you should use the roof of your house or the balcony of your flat to produce clean solar power yourself. That would necessarily be a less complicated venture, but, as you know, every journey begins with a first step. I live in Portugal and am the editor of this magazine. I originate from Germany, where I went to school, studied and learned the profession of a journalist. Then I decided to fulfil a dream that I had had ever since my early days. I bought a sailing boat with the first fee that I received as a television director and sailed out to sea and into the wider world.

That’s how I came to Portugal: with the wind. This was as far as I got. Back then, more than 30 years ago, the climate was already changing and, with it, the winds, the weather and the sea. And, since then, I believe that we have been beating about the bush and not doing enough to improve the situation. Because, already at that time, it seemed to me that the climate was getting warmer and warmer: the summers were getting longer and longer, and the winters shorter and shorter. It rained more irregularly, sometimes much more than before, and then less and less. But then the wind began to change direction more frequently and, instead of rain, it brought us nothing at all. Anyone born in the last 25 years has no way of comparing what we are experiencing now with the climate as it was before, especially as far as the conditions at sea are concerned. I was living on the same sailing boat that I had arrived upon, and my wife was pregnant. So, we came ashore to prepare for the birth of our child, and we were warmly welcomed by our nearest neighbour in the Monchique mountains. One morning, he brought us a gift for our new home: two buckets of food – potatoes in one bucket, tomatoes, peppers and onions in the other. What kind of friendly world had we stepped into? Portugal! We lived far away from civilisation, amid the nature of the mountains, without electricity and with running water that came from a spring. Everything seemed right with the world, our world, our new Garden of Eden.

We were soon brought back down to earth. We were hit by heavy rain, and a stream burst its banks after a thunderstorm. leaving nothing as it had been before. The orange grove, with its 60 trees, was all washed away. Within six hours, we had suffered as much as half a year’s rainfall. The mountain stream, which was normally less than 30cm deep, burst its banks and rose to a depth of six metres. The neighbours saved themselves by moving up onto the roof of their house. We were deeply shocked. The harbingers of climate change were announcing the doom that awaited us. And we were beginning to focus our attention even more intensely on the causes when the whole forest around us went up in flames the following summer. This completely changed our view of the world we lived in. What could we do about it?

The greenhouse gas effect.

From the day of that first forest fire, the idea of freeing myself from fossil fuels and no longer emitting CO2 into the atmosphere around me, freeing myself from the evils of our energy-intensive societies, began to develop within me. This idea was immediately given a roadmap. My goal was very clearly defined: I wanted to become climate neutral, and, combined with this, was the question: how can I possibly hand over my world to my children, when it will be so much worse than the one that I inherited from my ancestors? I was concerned about nothing less than creating the conditions for a good and sustainable life on our planet. And, I wondered, can I change anything at all? So, I started with a first cautious step, because I believe in the power of small, well-considered steps, and in the fact that we have to question ourselves, every day, more and more.

Step 1: How do I become energy-independent?

I no longer buy anything from China or the Far East that I can’t buy from local, regional or national producers. Travelling short distances reduces CO2 emissions. So, the first step is to instal at least one tracking system on your property with 20 solar modules of 430 watts each (as of 2024). I buy them, for example, from the Meyerburger company in East Germany, or directly from their headquarters in Switzerland, at https://www.meyerburger.com in Gwatt (Thun), or from the Spanish solar manufacturer Eurener in Valencia: https://eurener.com. They still exist, these last European solar panel manufacturers.

So, find out if you want to free yourself, like I did. Don’t give up, and ask your bank manager for advice. Because you want a solution: you need to find financing for your solar power system.

Around eight kilowatts of power should be enough to start with, which you can feed into the electricity grid, and then, in this way, you won’t need to buy a lithium-ion battery to store the electricity. At the same time, you can sign a mutual supply contract with a green electricity producer. For example, in Portugal, with https://coopernico.org or, in Germany, with BürgerEnergieGenossenschaft Losheim am See: https://beg-hochwald.de and then you can sell them the electricity you produce with the solar panels. And you can also become a member (comrade) of theirs, or look for another energy cooperative in your area. Make yourself free. Become independent. You will soon understand that you are growing with this first step…

In Europe, there are more than 1,500 energy co-operatives in Spain alone. You will realise that you produce more clean electricity with 20 solar panels than you can consume yourself and you will also earn good money from this. You can use this to pay off the possible loan – for example from the GLS Bank in Bochum (Germany) – that you took out with this green bank to pay for the cost of the tracking system. Incidentally, you can also deduct the cost of the investment loan from your taxes. I’m talking about a manageable investment of around 15,000 euros. Stay alert and keep yourself informed. (https://www.gabv.org/)

When I bought my systems in 2010, almost 15 years ago, I was still paying 22,000 euros per system. I bought two tracking systems and made a sustainable investment in my own way. This shows how far the prices for solar modules have fallen in 15 years. Such a system pays for itself after around four and a half years. Then the rest can be paid off with the money you receive for the electricity feed-in. In my case, the remaining ten-year period of electricity feed-in was all profit. I was able to make good use of the income from the sale of electricity both then and now. In Portugal, you earn a pittance as a journalist (and I didn’t want to become corrupt). What’s more, I had just had to ‘repair’ another forest fire. We, the Esgravatadouro co-operative in Monchique, built a potential sprinkler system for the new forest that we are currently planting. Because the forest fire that I had experienced back then was not the only one I endured. With a lot of luck and even more experience, I have now survived five forest fires. But more about that later.

Step 2 Flying was yesterday – travelling by train is tomorrow.

Protecting nature is important to me, a matter close to my heart. Because anyone who has watched it go up in smoke and then dissolve into ashes becomes more and more sensitive every time.

When it comes to mobility, that is where your freedom really begins. It was a few years ago when I made this clear: flying on holiday or to an appointment for an interview is something that now belongs to yesterday. And, for the next few years, I resolved to simply get to know Europe – our own old continent – even better. Less is more, and, in particular, slower is healthier. Since then, I have avoided flying wherever possible.

Start thinking about how to get from Portugal to Norway without petrol, diesel or paraffin. I had to travel to Norway to do an interview. I just have to tell you this story because it’s a good example of a critical approach to the topic of zero emissions.

On 1 August 2018, I wanted to have a conversation with the famous psychologist and economist Per Espen Stoknes from the Club of Rome about his still extremely important book entitled “What do we think about when we try not to think about Global Warming”. So, I got on the TVE express train in Huelva, the first Spanish railway station after Portugal, and off I went at speeds of up to 320 km/h via Madrid and Barcelona to Girona – electric and almost emission-free, of course. I took a break and spent the night there. Shortly before eight o’clock the next morning, I boarded the TGV, which took me via Lyon to Paris, and from the Gare de L’Est on the ICE via Saarbrücken to Frankfurt and Fulda – all in a single day on the train from northern Spain to the centre of Germany. Why do I need an aeroplane, I asked myself, when I can travel by train with almost no CO2 emissions?

On 1 August 2018, I wanted to have a conversation with the famous psychologist and economist Per Espen Stoknes from the Club of Rome about his still extremely important book entitled “What do we think about when we try not to think about Global Warming”. So, I got on the TVE express train in Huelva, the first Spanish railway station after Portugal, and off I went at speeds of up to 320 km/h via Madrid and Barcelona to Girona – electric and almost emission-free, of course. I took a break and spent the night there. Shortly before eight o’clock the next morning, I boarded the TGV, which took me via Lyon to Paris, and from the Gare de L’Est on the ICE via Saarbrücken to Frankfurt and Fulda – all in a single day on the train from northern Spain to the centre of Germany. Why do I need an aeroplane, I asked myself, when I can travel by train with almost no CO2 emissions?

Then, I freely admit, things became a little difficult. In the meantime, we were all well aware of Deutsche Bahn’s problems. I was still on time from Fulda via Hanover to Hamburg. But getting from there to Gothenburg via Copenhagen was difficult because the train from Hamburg refused to budge. It had broken down. I waited for hours for a replacement train to be provided. If you’ve lived in Portugal for as many years as I have, waiting is no longer a problem. The new train arrived at some time in the afternoon, but instead of arriving in Sweden at five o’clock in the afternoon, I didn’t get to Gothenburg until two in the morning. On the fourth day, I travelled from Gothenburg to Oslo at midday and it only took four hours. Despite all that time on a train, I never got bored. Either the scenery was breathtaking – for example, taking the train onto a ferry and sailing across the Baltic Sea – or I found fellow travellers in the compartment with whom I could swap exciting stories. I am a journalist, speak three languages, and now make more time in my life for myself and for others in conversations, because I am quite sure that I want to avoid CO2 emissions and also because I can. The issue of no longer burning fossil fuels has become the top priority in my life. Everything else is now secondary. My internal clock slowed down. I had stopped taking part in the rat race of spinning on a wheel like a hamster. I slowed down and became more alert: I used my imagination.

During the whole of my train journey, almost 4,500 kilometres long, I only emitted 160 kg of CO2. I did the maths with the various CO2 calculators: I would have emitted more than ten times that amount by plane. I was travelling to Norway for three and a half days.

After that, I took a day for the interview and, a day later, I made my way home again. The trip there and back cost me a whole 220 euros with an Interrail ticket, plus 80 euros for seat reservations. Rarely have I felt as comfortable as I did on that train journey – travelling with time and not against the clock. On the way back, I heard the news at the station in Copenhagen that the forest back home in Portugal, in Monchique, was on fire again. A eucalyptus tree had touched a high-voltage power line and sparks had ignited the forest to the north of Monchique at temperatures of 44º Celsius. Man-made climate change had struck again, and human negligence had done the rest…

Nowadays, if I have to drive from Monchique in the south of Portugal, where I live, to Lisbon or Porto because I want to do an interview there, or if I travel from Cologne to Minden in Westphalia by train, I know my emission values pretty accurately. For local and regional destinations, I’ve been using an electric car since 2016, which I can charge with electricity from my own solar power system, and it’s even free. Mobility for free! Neither the sheikhs nor Vladimir Putin will receive a single cent more from me. And you don’t even have to travel; you can also do it via ZOOM.

Nowadays, if I have to drive from Monchique in the south of Portugal, where I live, to Lisbon or Porto because I want to do an interview there, or if I travel from Cologne to Minden in Westphalia by train, I know my emission values pretty accurately. For local and regional destinations, I’ve been using an electric car since 2016, which I can charge with electricity from my own solar power system, and it’s even free. Mobility for free! Neither the sheikhs nor Vladimir Putin will receive a single cent more from me. And you don’t even have to travel; you can also do it via ZOOM.

In Portugal, a local journalist earns very little money. You have to double your wages in euros before you can spend them. But, in Portugal, the sun shines 300 days a year – for free. And since, in 2010, I had set myself the goal of becoming climate-neutral by 2025, I thought carefully about how I was going to do this, where exactly I was going to start and where I was going to end up. In the middle of the period – i.e. at the end of 2015 – I scrapped my petrol car and finally saved enough money to buy an electric car with government support at the beginning of 2016. In just under ten years, I have driven 125,000 kilometres without any CO2 emissions and saved more than 20,000 euros in petrol. Because the question of ecology is always also a question of economy.

Step 3: What I can’t measure … I can’t reduce – so, learn how to measure CO2.

I was looking for a Christmas present for my son. It had to be a present that wouldn’t leave any rubbish behind and would be something special. One morning, I woke up and knew exactly what it should be: a game, or rather, a test. The Kyoto Protocol of 1997, which 195 countries had ratified, and the UN Climate Treaty of Paris 2015 had influenced me significantly. In the following section, I will call the gift a ‘game’, and it is played like ‘Monopoly’ or ‘Mensch ärgere dich nicht’. When I think about an idea, I often take that thought to bed with me overnight. And, when I wake up, I very often have a solution.

My son and I created the game together. And how should it be played? If you take part, the referee allocates you an annual online credit from the ‘State’ of 3,000 kg of CO2, and you have to make do with that amount for 365 days. That was the requirement. Whoever still had a positive credit balance at the end of the year would win. Was something like this feasible?

The machine was a server with a programme that we pre-programmed for the players like an online account at a bank: there were several areas in which the 3,000 points would be spent more slowly or more quickly: mobility, nutrition, electricity consumption, home maintenance, heating and cooling, leisure and holidays, waste and recycling, and so on. I was inspired by a test organised by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) in Berlin and asked the subscribers of our publishing house, the readers of ECO123, if they wanted to play the game and compete with the other readers. I was looking for 100 participants for this test, who were gathered together little by little. The game began in 2019, and everyone undertook to complete an online form every weekend, which the computer then recorded, swallowed and processed – for over a year. At the end of the year, 15 of the 100 readers were still left in the game. 85 players had given up in the meantime. At the beginning, there was an equal number of women and men, young and old, Portuguese, British, German and Swiss. The most distant participant was a Portuguese woman who had married into a Norwegian family and subscribed to the ECO123 magazine there. Only three of the 15 participants ultimately succeeded in leaving a carbon footprint of less than 3,000 kg of CO2 at the end of the year. Three out of 100.

The machine was a server with a programme that we pre-programmed for the players like an online account at a bank: there were several areas in which the 3,000 points would be spent more slowly or more quickly: mobility, nutrition, electricity consumption, home maintenance, heating and cooling, leisure and holidays, waste and recycling, and so on. I was inspired by a test organised by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) in Berlin and asked the subscribers of our publishing house, the readers of ECO123, if they wanted to play the game and compete with the other readers. I was looking for 100 participants for this test, who were gathered together little by little. The game began in 2019, and everyone undertook to complete an online form every weekend, which the computer then recorded, swallowed and processed – for over a year. At the end of the year, 15 of the 100 readers were still left in the game. 85 players had given up in the meantime. At the beginning, there was an equal number of women and men, young and old, Portuguese, British, German and Swiss. The most distant participant was a Portuguese woman who had married into a Norwegian family and subscribed to the ECO123 magazine there. Only three of the 15 participants ultimately succeeded in leaving a carbon footprint of less than 3,000 kg of CO2 at the end of the year. Three out of 100.

Every Friday I sent out a newsletter with tips on how to win the game. And there was actually one participant who parked her car in the garage and travelled to work by bus and metro from then on. She also bought a small solar power system for her balcony and did her utmost to ‘burn’ as little of her credit as possible … And so she ate a vegetarian diet for some weeks and eventually also a vegan diet, and, at the age of 55, learned how to cook again and to analyse her electricity bill precisely. Over the course of the game, her diet had completely changed, as had her electricity consumption. She also reduced the amount of waste she produced by shopping at the weekly market instead of the supermarket, and all this happened in the big city of Lisbon. She avoided plastic packaging and started eating organic food, buying directly from the farmers and, of course, at the weekly market organised by the AgroBio association.

By constantly measuring our footprint on a CO2 calculator, we can take a playful look at ourselves and put ourselves in a position to constantly reduce our CO2 footprint…

Step 4: The bratwurst in Germany, the bifana in Portugal and the meat from the animal…

Difficult, difficult, difficult… our favourite habits always tend to make us return to the dead animal. I had repeatedly watched bullfights in Spain and Portugal and was keen to discover what they do with the dead animals. In Portugal, the bulls are not killed in the arena. The torture lasts a little longer. Bullfights in Portugal usually take place on Saturday evenings. The poor animal is then dragged onto a lorry and has to spend the whole Sunday bleeding in the sweltering heat behind the arena. The lorry is not driven to the slaughterhouse until early Monday morning. I wanted to know whether this was just a story (a fairy tale) or reality.

So, I got into my car, took out my sleeping bag and waited until the lorry with the tortured bull was driven from Albufeira to the slaughterhouse in nearby Faro early on Monday morning. I followed it. When I arrived at the slaughterhouse, I quickly put on a white coat and pretended to be a butcher, because I wanted to buy the meat of the slaughtered bull. Why? I had heard that you could buy cheap beef under the table at the abattoir for 4.30 euros a kilo and that the butchers then sold the meat back to their customers at a much higher price. I had had business cards printed so that I could pass myself off as a butcher. After my report, the abattoir was closed, presumably because they wanted to build a new IKEA store and a new shopping centre there.

I had always intended to stop eating meat, sausage and ham because I was becoming increasingly aware of the unbelievable torture that we humans inflict on animals. We love dogs and cats more than anything, but we slaughter pigs, calves and chickens by the millions every day. We hide everything about the so-called farm animal, the so-called fattening process, the rearing of animals with cheap soya feed from the Amazon, the antibiotics that are injected under the animals’ fur, the slaughterhouses, the mass killings and so on.

I have my grandmother to thank for passing on gout to me. Since 2018, I have no longer been able to eat meat or fish, and I no longer drink alcohol or eat seafood. In our kitchen, I prepare and eat potatoes, vegetables and vegetable fats such as our own olive oil and, for a while, I also ate animal fats such as milk, cheese, yoghurt, eggs and honey. We spend our time discussing whether or not we want to go vegan soon.

My footprint has become much smaller as a result. By going meatless and eating locally, I have reduced my CO2 footprint by 35%. Instead of buying potatoes from the freezer in a supermarket, such as chips with a CO2 emission of almost 5,000 grams per kilo (because of the electricity!), I grow my own potatoes at my own place. Emissions? 189 grams per kilo. The meat-free diet plays an important role in reducing your footprint. So, if you have a hectare of land, cultivate it with love.

Step 5 Shopping for groceries

Look at the small print on a yoghurt carton in the supermarket, or when you go shopping for other foods: always buy locally and, if possible, without any plastic packaging – and make sure you don’t buy anything from countries outside the EU. Stick to this principle and live by it. It will change your life for the better. You will feel better because your footprint will be smaller and smaller. Shop only once a week and save yourself a lot of unnecessary journeys to the supermarket by car. Swap the supermarket for the weekly market. You will then be able to enter into a relationship with the producer of your food. You will know how a cheese is made and where, for example it comes from. The yoghurt then comes from the farmer, and it comes in a jar. Next week, I’ll take the empty and cleanly washed jar and swap it for a new, full yoghurt pot. Here in the Monchique mountains, we still eat very locally.

The continuation will follow here next week…

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia