I recently bought myself an Interrail ticket for 224 euros. I used it to travel for five full days within a fortnight through half of Europe. The idea that I could stop here and there, get out and take my time, increased the sense of anticipation. And so I consulted the timetables of Portuguese and Spanish railways CP and RENFE. In doing so, I was amazed to discover that there is only one rail connection between Lisbon and Madrid (and back). Why? For the 600 km between the two cities, the train needs 13 hours. I realise that we in Portugal are somehow still living behind the times. I thought I could simply get on an Intercity train and travel in the morning from Lisbon via Madrid to Paris. No way. So I got a friend to take me to Huelva in Spain and travelled from there to Barcelona on the first AVE at a speed of 300 kilometres an hour, and then by TGV the remaining 1,200 km to Paris in less than six hours. My first destination was in Germany. I wanted to go to Freiburg, one of the most innovative German cities, in the border region between France, Switzerland and Germany.

I live in a village in the southwest of Europe. Twenty-five years ago, I bought a plot of land in the Monchique hills between the southern Alentejo and the Algarve in Portugal and built a new house on it. Even in those days, I had an idea about sustainability and a corresponding plan. I used cork to insulate the house. I used cork that was five centimetres thick instead of just three. The plan was to keep the summer heat of more than 40 degrees Celsius out of the living area. I used double glazing for the windows and doors. Outside shutters provided additional insulation to avoid having to install a power-hungry air-conditioning unit. I also invested in two solar tracking systems with 40 solar panels for self-sufficient electricity generation, the basis for a good, sustainable life. I use it to charge my electric car, among other things.

I have given up flying for ecological reasons. These days, I always do long journeys by train. Trains are powered by electricity. When our stressed fellow citizens suggest that aeroplanes are faster and cheaper, they forget the price that we and our children will have to pay for this, that planes are the biggest polluters because they release the most CO2 into the atmosphere. By contrast, trains can travel quickly, efficiently and almost emission-free between most European cities, just not (yet) in Portugal. In theory, it would already be possible today to board a train in Lisbon in the evening and to get off the next morning in Berlin or London after a good night’s sleep, or in Paris, Brussels, Rome, Geneva or Amsterdam. I set off on my journey to Germany because I am interested in current developments in sustainable house construction. An interview with the father of the solar energy-plus houses, the architect Rolf Disch in Freiburg, is on my schedule.

The Exodus

In Monchique, I am one of the new residents of a village where fewer and fewer people live, year by year. When I arrived in Monchique in 1990, there were still just under 9,000 inhabitants. Today, there are not even 5,000. The trend is downwards, and more than half the population is over the age of 60. A look at the statistics from the year 1974 reveals that that 12,000 people were still living in the municipality in those days. Where have all these people gone to? On a walk through the village, I notice that almost half of all the houses and shops are empty and are slowly decaying. A third of all the buildings are ruins, the historic convent, the Casa do Povo (village hall) and many shops. The figures I am using are already three years old. Since 2011, an average of 300 inhabitants have died every year; but there are only 50 new births per year. Of the approximately 100 young school leavers, half move away, among other reasons to find work. I estimate that Monchique could died out within one more generation – if nothing earth-shattering happens, in a positive sense.

People who do not take responsibility for their property can be dispossessed by the state or the municipality. Think of all the things that all the ruins could be used for? The state or municipality could give them away to young people for them to make habitable again, to restore them in ecological and energy terms, and, in this way, to save the village of Monchique from dying out. On the train, I prepare myself for my interview, and read a bit about energy-plus houses. What makes them different is that they have a long useful life, are energy efficient in construction and are supplied with renewable energy, have low running costs, and contain a lot of solid wood. At their heart are thermal and sound insulation and low energy consumption. With PlusEnergy, houses become power plants. They produce more energy than their occupants consume.

Why not embark on a constructive and sustainable policy of village renewal all over Portugal in order to slow the exodus of young people from the countryside to the cities? Attractive training places and jobs would have to be created anew in the rural areas, and a sustainable concept for revitalising the local economy would need to be drawn up, presented and implemented in the municipal councils. Historical crafts such as those of the shoemaker and the traditional mason, weaving and carpentry would have to be promoted. Traditional old professions, and new, modern ones in the energy sector and IT area would together have to find a way, not only of keeping young people in their villages, but of initiating a movement in the opposite direction: from the city back to the land. A movement of this kind is starting in countries in central Europe: in Holland, Germany, Switzerland, even in Britain. The declared goal of a modern transition village on a traditional foundation is complete self-sufficiency. But in Portugal, to put it kindly, we are still living a bit behind the times sometimes.

This could be changed. Monchique’s young mayor Rui André (40) recently had an idea with which he made it into this edition of the magazine. Whether he produced this idea just for electioneering purposes or whether he really wants to continue implementing it after the local elections in 2017 only he can know. The top man in the village is offering new young residents who plan to buy a derelict house in Monchique and then live in it a grant of 5,000 euros towards the purchase price of the house. In addition, he will support the restoration and renewal of a derelict house with up to 15,000 euros. Read more about it in our interview with him on page 48.

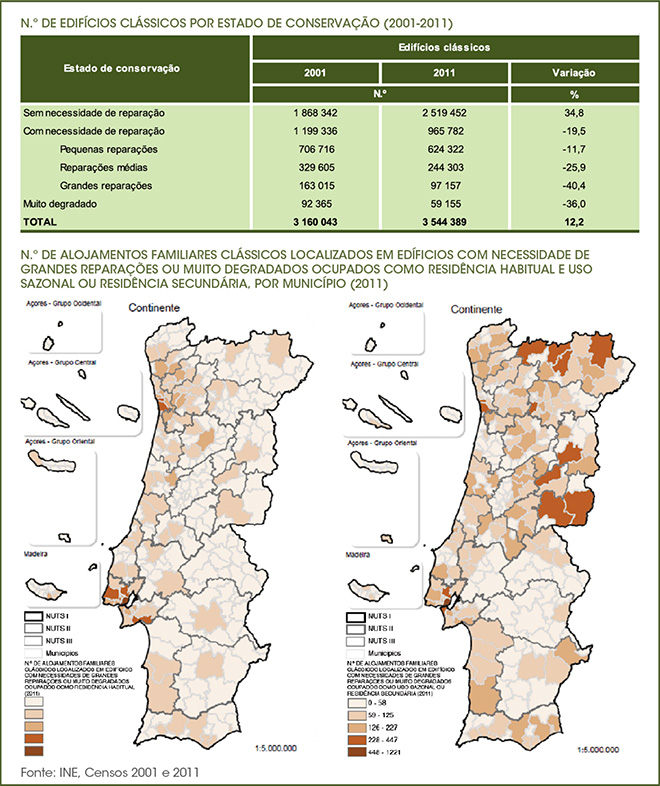

Almost a million houses must be renovated

In 2013, the National Statistics Institute (INE) published its most recent long-term study about the state of buildings and residential properties in Portugal between 2001 and 2011. Interesting figures emerged from this. Of the total of 3,544,389 residential buildings in the country, 965,782 are unfit for habitation, in some cases very unfit. Both the function of roofs and the insufficient insulation of walls and windows were criticised, along with unhealthy ways of building, the infiltration of damp and harmful formation of mould. The municipalities of Almada near Lisbon, Sintra and Loures, Chaves, Castelo Branco, Guarda, Idanha-a-Nova, Covilhã, Lamego, Tarouca, regions such as Grande Douro, Trás-os-Montes and some municipalities of the Algarve were listed, such as Monchique and the hinterland of Alcoutim, Tavira, Loulé and Silves.

Every bad piece of news can become a good one. Where a lot of things are in a bad state, there is huge potential for investment and job creation. It can actually only get better. There are enough challenges. What is lacking is individual initiative and the encouragement of whole regions to implement the sustainable restoration of housing. These important and correct investments for their part could lead to sustainable long-term prosperity. As prosperity never emerges first in the balance of a bank account, but in knowledge and in the implementation of innovative and sustainable ideas and plans, I travel to Germany, a country that reinvented itself within two generations out of the ruins of two world wars. The point of the journey was to come back to Portugal with some ideas. PlusEnergy, I see in my architectural reading, offers solutions that go beyond the insulation of the outer façade of a house, heat recovery in winter and cooling in summer, and uses solar installations on the roof to generate electricity. As is well known, the sunshine in Portugal is free for everyone.

If we imagine the era in which we live at present as the transformation from a linear past into a circular future and question the present, and ask what is actually lacking for a good life in the place and in the manner in which we live … what would the answer be? Investments in our ruined homes so that they would keep us healthy in the future, because they were well insulated and produced energy instead of just consuming it? Jobs that were meaningful and properly paid? Communal institutions, such as municipal councils and energy suppliers, that would work in less bureaucratic and simpler manner in order to make us happy? How we would all have to deal with our natural surroundings in order to avoid forest fires in future?

Green village of Monchique?

What else is needed for a good life, I wonder, as the colourful autumn landscape of France flashes past me in the TGV? If we look closely at how we imagine our country and our municipality, don’t we get creative ideas and plans for a better country, a better village? And why shouldn’t our country and our village be better? Because we would then feel better and happier between our own four walls and under our well-insulated roofs, in our gardens and in our community. This in turn would slow down the migration from the countryside to the cities and from one country to another. ECO123 wanted to know from the Ministry for the Environment whether it could imagine helping to initiate such projects, and so interviewed the Secretary of State José Mendes at the Ministry in Lisbon. Read the interview on page 38.

After two days travelling by train, I arrive at the main station in Freiburg, check in to my hotel and am given free tickets for all tram journeys in the city. That’s how I get to the Vauban housing development, and stand on the third-floor roof garden of the so-called “Sonnenschiff” (Sunship), an office block and business premises, and look out over hundreds of solar modules on the roofs of the houses. The architect of the solar development is already waiting to introduce me to the pilot project of the sun houses.

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia