Saturday, 1st January 2022.

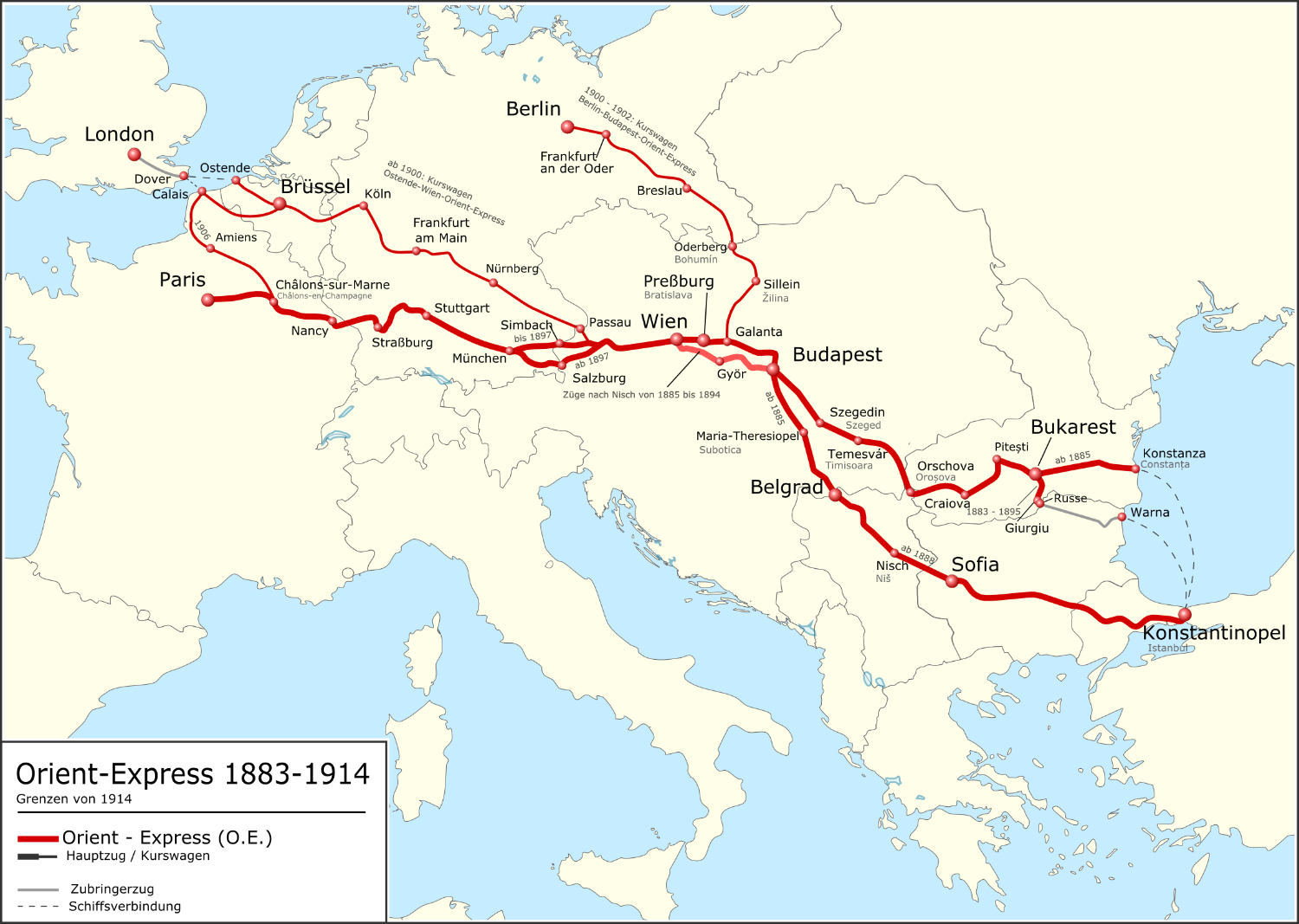

As early as 1883, long before the foundation of the European Union, a train connected France, Germany, Austria and Yougoslavia with Turkey: the Orient Express. Its passengers would cover some 3000 kilometers in three days: from Paris via Vienna and Budapest all the way to Varna, later on also from the Alps via Venice to the Danube and into the powder keg that was the Balcans. It was considered the train of kings, diplomats, writers and other legendary passengers in Mata Hari, Josephine Baker, Marlene Dietrich and Agatha Christie, who was inspired to write „Murder on the Orient-Express“ aboard this very train. With its sleeping and dining cars it offered a level of luxury unheard of to date.

From its inauguration in 1883 to 1977, when the Paris-Istanbul line was given up, the Orient Express was an ostentatious and glorious train. Yet it also lived through decay, revolutions and wars. As the only train allowed to cross the Iron Curtain during the Cold War it became the means of transport of choice for workers and immigrants.The TV documentary The Orient Express – Vintage on Rail, which you can watch at https://www.arte.tv/de/videos/077320-000-A/der-orient-express/ looks back on over a century of railway adventure, using the insights and testimonies of historians, historic railway restorers and collectors. The cultural historian of industrial heritage Artur Mettetal, who specialises in the restoring of historic trains, shows us what is left of this luxury train in Europe but also restoration workshops and 13 unusual carriages, parked and simply abandoned at the border between Poland and Belarus. The European broadcasting companies ARTE and BBC France send their audience, in German and French, on a border-hopping trip exploring the myths and the reality of this legendary train. So why is something that not even 150 years ago started off to great success, so terribly difficult to achieve today, in a Europe without borders?

What is the EU’s stance on switching from road to rail?

Before the launch of the European Green Deal in 2019, the European Commission prepared a communication titled ‘A Cleaner Planet for All’. It named rail as the most energy efficient solution for medium and long-distance freight transport and proclaimed that the Trans-European Rail Core Network (TEN-T) would be completed by 2030. This was in line with the Green Deal’s call for a 90% reduction in transport emissions by 2050, in order to achieve its climate goals.

The EU Commission has promoted trains as a sustainable alternative to road and air travel for tourists, commuters and freight. The EC named 2021 the “year of rail”, and a special EU PR train (the Connecting Europe Express) crisscrossed the continent from 2 September to 7 October, stopping in over 100 cities. Much more investments are made into railways than before. And yet, Europe’s rail network suffers from long-term neglect in many areas. Long-haul train networks are a great example: there are very few synchronised timetables, and services tend to stop at national borders with little cross-border convenience.

So, what is the EU actually doing about rail?

Even though the mantra in Brussels has been ‘road to rail’ from the 1990s onwards, the EU’s policies have prioritised the road and aviation sectors. Even if investments in the railway sector are growing, infrastructure deficits and maintenance gaps are not improving fast enough. In some cases, (e.g. the Peloponnese in Greece) lavish investment in motorways has shut down the existing train network and killed the chances of its revival because there is not enough transport demand to support both.

In recent years, the EU has adopted four railway packages which — according to the Commission — aim to open the railway market to competition, increase the interoperability of national railway systems and define the framework for a Single European Railway Area (SERA). This includes such requirements as ‘wheel and track’ separation (having separate management for railway infrastructure and services). The fourth railway package came into force in 2021, but its implementation has been uneven as member states have chosen to implement it in different ways.

Moreover, the EU’s current tax policy is another factor preventing the emergence of rail as a real and credible alternative to road and air. The aviation industry across Europe has historically faced no to limited taxation. There is no tax on fuel, and VAT exemptions on airline ticket taxes in many European states. In contrast, VAT is still paid on tickets for many cross-border European rail services.

Meanwhile, the EU Commissioner in charge of Transport, Adina Vălean, doesn’t see her role as one that should mandate cross-border connections. “Cross-border railways need more cooperation between neighbouring member states, but we cannot oblige them to subsidise something which is not commercially viable,” she said in an interview with Investigate Europe.

Are individual Member States responsible for the current state of cross-border railway?

Partially. Rail transport in Europe was once the state’s job. The state railways didn’t have to make a profit, but they had to ensure the supply. This changed in the 1990s. Driven by the belief that competition would revitalise the otherwise underfunded railway system, the EU member states were supposed to begin the privatisation process and attempt to separate rail infrastructure and its operation. While smaller countries in the south and north implemented full separation, the bigger ones like Germany and France created holding companies that still integrate the “wheel and the track” under the same management. With a new focus on profits, however, many less profitable routes were discontinued, including shorter distance routes in France or cross-border night trains in Germany.

Europe has been developing a network of transport infrastructure (TEN-T) for decades. As part of this undertaking, the rail improvements are especially costly — amounting to at least €500 billion. Only a fraction of this investment will be paid for by the EU, the rest will have to come from member states’ own pockets. And it is precisely when cross-border investment is involved that member states are reluctant to invest, concentrating for political and economic reasons on developing the domestic network. It seems that member states are reluctant to spend money on something that is not specifically in their national interest, and the EU does little to convince them otherwise. Adina Valean, the current EU Commissioner for Transport, told IE that “if something is not commercially viable, we [the EU] cannot force it to exist”.

Some experts IE talked to also indicate that one reason for the fragmentation is military security and the lingering memories of two World Wars. Troop transport is most effective by rail so the railways are a strategic infrastructure that states want to control nationally.

Why can’t we have more non-stop rail connections between European countries?

Even if the political will for non-stop cross-border travel existed, there are many operational and technical challenges. These include trackside interoperability, lack of standardised electrification and signaling systems, rules that are specific to some member states and even language barriers (train drivers need to speak the language(s) of the country they are driving through at least B1 level).

One significant obstacle to the Single European Railway Area is the slow implementation of the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS), which is a unified safety monitoring system that will continuously supervise the speed of each train according to track and train data. It has the potential to lead to better traffic management, thus resulting in higher capacity on the same tracks. However, as of now, it has been significantly delayed. As Josef Doppelbauer, head of ERA points out in an interview with Investigate Europe, “[Today], A Eurostar train travelling from the UK from London via France and Belgium to the Netherlands and Amsterdam currently needs nine different train control systems.”

Just in recent years: the Polish railways have bought locomotives that cannot run in neighbouring countries; the Danes have bought locomotives that can only be put on rails in Denmark and Germany, so when the Swedes indicated they would run a train from Stockholm to Germany, the Danes said they could not help, so there were no trains. And Deutsche Bahn’s new ICE 4 fleet, which runs from Berlin, has only one power supply system, so trains can only run in Austria, Germany and Switzerland and nowhere else.

What does privatisation have to do in all of this?

In the 1990s, Europe’s railways were state-owned, but over time, with increasing competition from other transportation modes (cars, trucks, airlines), it was clear that the railways system was in decline. As one diploma wrote in Politico in 1999, “The railways are being run in much the same way the Soviet Union ran everything. The Commission wants to create a single market in rail and have railways function as private companies.”

It was against this backdrop that a spirit of liberalisation emerged. With its railway packages (four in total), the EU tried to help private companies enter the market. The first package required railway companies to be split up so that the operations and infrastructure were handled separately. The idea here was that competition would help the rail industry grow and lead to better service, but implementation has been patchy.

Benedikt Weibel, head of the Swiss Federal Railways (SBB) from 1993 to 2006 points out, “One of the big mistakes was that the European Commission had the same recipe for every sector: energy, airlines, telecom, postal services, and railways. Every one of these five big sectors is completely different.”

Countries responded differently to this mandated ‘wheel and track’ separation, with many not applying the provisions of the railway package that were inconvenient for them. Some (like the Netherlands and the UK) fully separating while others (Germany and Italy) had partial integrations. Thus, today in Europe, the privatisation of national railway markets is at very different levels, but in most of the countries, the biggest players are monolithic state-owned companies, at least for passenger services. In some places, services have improved, but not uniformly.

What can switching from a short flight to a train trip do for the climate?

The transport sector saw an increase in greenhouse gas emissions by 30%. And nearly none of that was generated by rail. Aviation, at the same time, accounts for about 12-13% of total EU transport emissions, a bulk of this number being long haul flights over 4,000 kilometres.

Short flights under 1,500 kilometres make up 25% of the total sum. Not a lot, but if the EU were to ban short haul flights and encourage a shift to rail (wherever a connection under six hours exists), Europe would already save 3.5 million tons of CO2 per year — the equivalent of Croatia’s annual emissions — according to a Greenpeace study. There are also the other impacts of aviation (like NOx and water vapour), that are proven to have two times more of an impact on climate and people’s health.

Just ditching air transport will not get Europe to its climate goals. But combined with a switch from road transportation to rail, and more incentives to develop a working railway system, there is a chance to significantly decrease the environmental impact of transportation.

Are there any positive examples of how cross-border rail can work?

It’s easier to find positive examples of a well-functioning rail system on a national level (like in Switzerland, and the Praha-Ostrava line in the Czech Republic) than across borders. But there is one hopeful precedent that is worth a mention: the Austrian ÖBB’s NightJet trains. Improving connections over long distances is inherently tied to big investments in high-speed trains, costly infrastructure and — easier said than done — long-term planning.

Considering the above, night train services can already provide a quicker alternative, and ÖBB decided to bank on them. After the biggest European operator of night trains, the German Deutsche Bahn, terminated all of its night services, the Austrian railways stepped in and quickly dominated the market. NightJet became profitable in its first year of operation, several years ahead of its original assumptions (though most probably not without the help of the Austrian government). Today, the NightJet network covers ten European states, and has many of its routes passing through three different countries. Despite the losses induced by the pandemic, it plans to expand its network and grow the number of night train passengers by up to 50% by 2025. In 2021 the company launched Vienna-Amsterdam and Innsbruck-Amsterdam connections. In December 2021, Vienna-Munich-Paris should follow. Over the coming years, the plans are to extend the network further, and working closely with partners.

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia