On a Sunday in October in this warm and dry year, at the tail end of a summer that shows no signs of wanting to end, I pull the door shut behind me, lock it, shoulder my backpack and start walking east, with my dog for company. I‘ve taken a week‘s time out for myself: a week with no computers, a life without Internet. In reality I want to take the track starting right behind my house, a trail leading into nature or, well, what is left of it after the great forest fire of 2018.

After a few kilometres there is this hidden waterfall very few people know about, which pours out its refreshing liquid from a height of nine metres into a natural basin, like a shower. This is a place where you can take a dip, undisturbed, and feel like Adam and Eve. Will the brook still be flowing?

The dirt track leads cross-country through valleys we call barrancos and up again over the foothills. Up, down and all around: these are footpaths that only a few in the know are aware of. Geographically, the barrancos run from north to south; within them, mountain brooks flow downhill. But because this hike starts on an autumn Sunday, hunters too are about, on their legal hunting day. In the distance you can hear them shooting since dawn: boom boom, in the way of an advancing frontline. I decide to avoid the risk of finding myself facing a rifle loaded with lead shot with my dog and we take the tarred road from Caldas to Fornalha. That’s six kilometres.

After a short while we meet a few goats belonging to our neighbour Zé Eduardo. Zé too is walking cross-country with his motley flock. Coming towards us with his goats and a few dogs, he too is taking the tarred road where the animals are enjoying the herbs to the left and right of the way, moving towards us grazing. Cars? Nope. A path devoid of humans leads from west to east past the last inhabited houses. Sometimes I have to convince myself that something like nature around me still exists really, a nature that I can feel I belong to. In truth, journalists should leave their office as often as possible, escape the virtual world and dive into reality. This has been my professional motto for many decades. Which is why in my free time I dig into the soil, cultivate my own potatoes and vegetables, engaging in something very similar to permaculture. I want to be able to do more than, well, just write stories.

DAY 1

Thirst – an unexpectedly great one

The goats are heading straight towards us. Max, my companion and a dog I’ve enjoyed a deep friendship with for the past six years, already knows the procedure and I ask him with a hand gesture to sit down, so he doesn’t sow confusion in the small flock. The two of us are standing quietly at the side of the road, waiting patiently to see which way the goats will decide to turn. Some turn around, others move out of the way, and yet another few come towards us, inquisitively. The flock seems to be breaking up. Standing in the shade of a cork oak, the shepherd is just finishing a phone call. Even a part-time shepherd always keeps an eye on his animals. Shouting instructions, he encourages his animals to pass us, and the goats get back into line, to avoid us as best they can and to leave us behind. The dogs are helping him watch the goats. We too continue on our way.

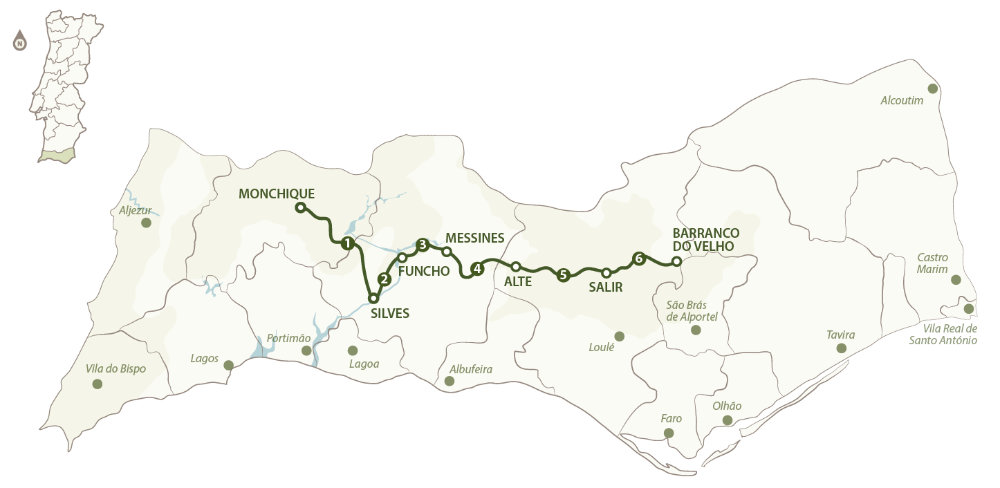

With the curiosity of neighbours he asks us „right, so where are you off to?“ I name the Spanish border as the destination of our hike spanning several days, a little over 180 km. We want to spend a few days crossing the countryside, measure and photograph the consequences of the drought, and also collect acorns and other seeds to plant new trees in our forest, which suffered severe damage after a forest fire. The autumn is the perfect season for this. At home I’ve set up a small nursery, with many saplings at the ready in their pots to be bedded out in the wintertime in our new forest garden – to replace some of the large old trees burned to death in the fire. Others we managed to save.

Having tidied up the area, now we can start planting new young trees. Bringing back genetical variety to local flora only works if seeds and acorns of many different tree species are bought together from other regions to grow in their new home. This also brings back the birds, providing them with nesting places again as well as with a safe refuge, and that in turn brings back other animals. One of the birds making its home here is the Bonelli eagle, a protected species of raptor. If, oh if it would finally rain properly again! Instead the sun is shining all day long, producing heat and dryness: it’s simply far too warm for the season. You can only plant trees in moist soil, so roots can find support, humid nutrients and the minerals dissolved in it. The months suitable for planting are December and January.

The newly-planted young trees have to use the time till the next summer starts to drive their roots deeply into the earth, to enable them to find humid soil in the deeper layers of the earth even in several months of dry summer. Alternatively you have to irrigate them artificially all through the summer, which involves other risks and dangers. It’s late October now, and the rainy season should long have started – as it does every year; still no rain is falling yet, and so the calendar registers the sixth month in a row with no precipitation since May. The summers are getting longer, the winters shorter. Our neighbour with the goats wishes us a good time, not without mentioning that he’d love to join us. But too many other commitments, professional and private, mean that he has no time.

Heading off again, we are soon overlooking the lower-lying hills of the Algarve. The panoramic views of the Atlantic provide a unique hiking cinema all the way to the horizon. It’s still five to six hours on foot downhill to Silves, the destination of our first day, which is nestling behind a tangle of hills in front of the sea. Silves is an inland town.

Walking normally, humans cover an average of three kilometres an hour. We are hiking in an area that was once nominated as a Network Natura 2000 by the EU.

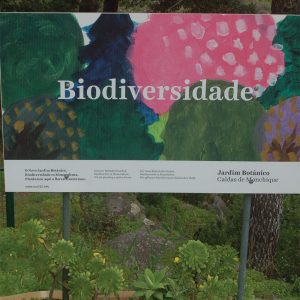

To the right and left of the path and up the mountains form part of protected biodiverse nature. Around 80% of the Monchique mountain range became part of the Network Natura 2000, which is not allowed to feature any eucalyptus monocultures nor invasive tree species such as acacias. So who planted these monocultures here to an industrial level, who authorised them? As far as the eye can see the only tree species growing here is eucalyptus, which is felled every eight to nine years in order to turn it into paper, or which occasionally burns down, leaving destruction in its wake. Once eucalyptus and acacia forests are ablaze, we know that both tree species will return, in their thousands, as soon as the following year, displacing other species of trees, as they shoot their fire-resistant seeds up to a hundred metres high into the air. This is the way invasive plants propagate.

„The Natura 2000 network extends across over 18 % of the land area of the European Union and over eight per cent of its marine area. This is the largest coordinated network of protected areas in the wold, offering a refuge for the most precious and threatened species and habitats in Europe,“ is what I’m reading. So what exactly is happening here in Monchique? In collaboration with the relevant authorities and the government, Portugal’s paper industry has carved out a space right here where the law doesn’t apply, transforming the area with the SITECODE PTCON0037 into an industrial forest for eucalyptus, used for making paper. This has happened in all secrecy over many years. The forest, a resource provider?

When eucalyptus is harvested, only a few weeks later already the naked, cut stumps produce new sprouts, which, in the way and shape of a perpetuum mobile develop into a new trunk with branches and new leaves. Nothing can stop the eucalyptus doing what it’s doing, unless you rip out a sapling including its roots with your hands, as if it was a weed. Amongst all the known tree species in Europe, eucalyptus is the strongest. It grows faster, its tap roots reach the groundwater and suck the soils dry. Autochthonous tree species cannot compete in any way, being a lot slower and frugal. In practice, I’ve had to watch this for many years, every year. Everything around planted eucalyptus is left behind and dries out over the course of the following years. No other species of trees will grow where there is a stand of cultivated eucalyptus – except – yes, except another invasive imported African tree species, the acacia. That one is similarly dangerous for the semi-arid vegetation of the Algarve where it only rains in winter of course, while the countryside remains dry for months over the summer.

The rainwater of the winter has to last for the entire summer. Which is why in the olden days people would store the winter rainwater in a cistern, to create water reserves for summertime. Acacias however have both tap roots and shallow roots and retrieve the last water from all layers of the soil, which young native trees such as cork trees, chestnuts and umbrella pines only reach after years of slow growth. Acacias manage to suck up the groundwater for their own use from unfathomed depths of the soil. Industry giants including The Navigator Company and Altri cover Portugal with eucalyptus, because that’s the raw material used to produce paper. In this way the paper industry has already transformed over a million hectares of forest in Portugal, felling autochthonous trees species and replacing them with eucalyptus plants. Eucalyptus however has another property that native trees don’t possess: its volatile oils worsen a forest fire, burning like petrol.

Once a forest fire has reached a eucalyptus forest, attempting to extinguish the fire is usually pointless. During a public hearing in 2019, the commander-in-chief of the fire services explained to anybody who was there and wanted to listen that an industrial eucalyptus forest which has caught fire is near-impossible to save using water. In Monchique, eucalyptus stretches out across many square kilometres.

Above us we see the Picota summit, 776 metres above sea level. Sometimes it’s visible, at other times it hides between two valleys. It’s in one of these barrancos that our Botanic Forest Garden is being set up, with a variety of several hundred native tree species. This pilot project serves to illustrate the native forest the way it was before the forest fires, as described in the Network Natura 2000. A living nature museum?

We are walking from west to east now, at an altitude of 300 metres. It’s still an hour and a half to Fornalha, which has the first publicly accessible water source. My idea is to walk from one spring to the other, so my dog too will get enough to drink. I myself have made space in my backpack for two large bottles of water, food for several days and spare clothing, as there is no grocery store to be found on our route for miles.

Only in the evening, arriving in Silves, do we dive once again into civilisation with cafés, restaurants and grocery stores. A backpack for long-distance trails has different kinds of storage space: two water bottles within easy reach to the right and left in two pouches, while at the very bottom I’ve placed my sleeping bag. Further up a second pair of trousers, several t-shirts and underwear, a jumper and a small first aid kit for walkers. Instead of shampoo and shower gel I am using olive oil soap that is biodegradable and produced locally by a lady soap-maker. Plasters, dressings, gauze bandages and disinfectant salve are part of that kit, as well as a pair of scissors, a variety of painkillers and calendula ointment for wounds.

It’s a hot autumn day, and it’s on the stretch until we reach the village of Fornalha that I finally find my rhythm, where hiking becomes a lot easier, synchronised with my breathing. The tarred road still bears the potholes from the Vilamoura Casino rally, which once a year sends their tuned cars haring around the bends – and lined by wild eucalyptus and acacias, which after each forest fire propagate and spread in an attempt, it seems, to own the entire countryside. The biodiversity of the protected Natura 2000 network however would look different, I mutter into my beard. Brussels should send an inspector on an excursion to the remote provinces to see for themselves what their protected areas look like in reality.

Not a sign of the native forest and its habitat. Brussels is far away, and paper is patient, I am thinking to myself. The forest fires ravaging their way through here in 1991, 2003 and 2018 have done a thorough job. In their wake, the sun and wind have eroded the ground and already blown away the most fertile layers of soil.

The people who once lived here moved to town many years ago, or passed away, taking precious knowledge to the grave with them, knowledge that a new generation today is lacking. Property rights too are becoming unclear over time, as no one feels responsible for the land anymore, while the houses fall to ruin and the underbrush reaches unheard-of dimensions: fertile ground for more forest fires. A vicious circle. No one checks zone PTCON0037 and no one wants to invest anything in sustainable development, as conservation keeps clashing with industrial exploitation.

At the entrance to the village, west of Fornalha, a pedestrian is greeted by a bench and a water tap in the shade of a carob tree. A few families are sharing this hamlet. An old workbench with a small sawmill, parked by the side of the road, renders silent testimony to any passer-by that once there was a carpenter running a flourishing workshop here. And what is the most important thing for a hiker? Clean water to drink and a bench for resting. However, a small sign warns against consuming the spring water; apparently it’s unsuitable for human consumption. Max doesn’t care what it says on the sign. He’s so thirsty that he guzzles the water from the basin until I’m able to stop him. Another hiker appears on the road, and we introduce ourselves. It’s Tom from England. As he’s friendly to the dog and Max too wags his tail, we decide to share this part of the way, as we both still want to get to Silves today. Tom too has brought too little water and will first need fresh drinking water. He asks the first person we meet in the village to top up his bottle with some water. A woman emerges from her house with a large plastic bottle and fills up his bottle. As the water from the village springs stopped being suitable for drinking a few years ago, the council provides each inhabitant of Fornalha with a five litre bottle „for human consumption“, as the mayor phrases it in an edict.

As for the spring water it immediately provokes diarrhoea with Max. That’s worrying. What happened here in Fornalha that even the pure spring water is now toxic?

For most of the time we’re on our own. No local would dream of travelling cross-country on foot. In two hours two lone cars cross our path. Then we’re on our own again. High above, a plane crosses the blue sky, leaving a white trail behind. About to land in Faro it’s now starting its gradual descent, which changes the sound of the engines. The Algarve hinterland is lying in front of us, abandoned. With every kilometre we recognise the dimension of the problem. Rural exodus. There’s not even an animal to be seen. If there aren’t any hunters about, the next danger awaits with the drought and the eucalyptus: forest fires. It’s midday now. There is hardly an inhabited house in this spot. Most buildings stand empty and in ruins. Only now and then we hear a few shots from afar. The autumn sun is shining through the fallen-in roofs of the ruins. The road is a grey band, broken here and there by potholes. On this particular Sunday, nobody, truly nobody is walking on foot overland, apart from two weird foreigners with a dog. At any rate that’s probably what this lady from Fornalha is thinking. While she doesn’t dare say that to our faces, it’s clearly written on her own. Why did they invent the wheel, to then use your feet… She only shakes her head when we tell her where we’re headed to today and still have to look for a place to stay… As if we had nothing better to do than hike overland where nothing seems to be happening. Only flies and planes carrying fresh meat, a name for newly arrived holidaymakers, cross our path. From Fornalha we take the abandoned road south to Laranjeira, until turning off into a little byway, heading downhill for the reservoir dam and the Odelouca river. The ground is stony and steep. And still, our path is lined by monocultures. Monchique ends at the river, which marks the start of the district of Silves.

Tom is a searcher just like me. He is working as Wooffer on a farm near Silves. We don’t talk much. A few days ago he hiked from Silves up to Monchique and is now on his way back. He’s looking for a plot of fertile land, as he plans to turn his back on England and buy a house in Portugal. There’s nothing better than to roam the landscape on foot and observe it, stopping here and there to check the water situation. Those buying land here in the Wild West of Europe need water, a spring or a capped spring, as water is everything and there is nothing without water. At the same time, our water supplies are dwindling during our trek. It seems we’ve not taken enough water and we are feeling real thirst. Crossing the only bridge up here over the Odelouca river, we are leaving the Monchique mountains. It’s another 15 km to Silves, so at least a five-hour „stroll“. We start to climb up to another ridge, gaining the foothills. In the evening, probably just before darkness falls, we’ll reach Silves, if we manage to source some fresh water from somewhere.

Max, half German shepherd, half Rafeiro Alentejano is a clever animal. In order to slake his thirst, he is always trotting ahead of me to then wait for a few moments in the shade of a medronheiro bush. That’s a serious sign of his thirst. Dogs of his kind are always travelling mindfully, looking after sheep and protecting people. They are like trappers, always a few steps ahead to check out the lie of the land, and if the coast is clear they come back, only to start running ahead again. Max walks the stretch I walk twice. If I’ve walked 25 kilometres at the end of the day, Max will have walked at least 50, always to and fro, back and forth. If Max is now looking for shade it’s a serious sign that he’ll have to economise his forces, that he’s tired and thirsty. I give him some of my water which he guzzles down greedily. Then, all of a sudden, in the lonely landscape we come across a house with a wonderful vegetable garden and water. Many of the older locals are past masters in subsistence agriculture. They’ll take the dung from their donkey to loosen the soil. They keep a few goats and always have milk and cheese in the house. The chickens are roaming free, fertilising the land. So once more a woman appears with a five-litre plastic gallon to serve us. The foldable bowl I carry in my backpack for Max she pours full to the brim. Thirst is starting to turn into a real torment.

We continue on our way, an old pilgrimage trail that today is called Via Algarviana, but which has been the old St Vincent’s Way since the fourth century. It leads from Valencia in Spain through the entire Extremadura region to the Portuguese town of Mertola, before taking the pilgrims via Alcoutim and Cachopo, Salir and Alte to Silves and Monchique, and from there to the end of the Old World at Sagres and the southwestern Cape. We are walking the way backwards, in the opposite direction, from west to east. A trip on foot like that would sometimes take weeks and give anybody enough time to turn inwards and fall into meditation mode. Hikers have all the time in the world to take a closer look at the land and to sharpen all their senses that got blunted in the hullabaloo of a town. You’ll meet people doing the same and might walk a few stretches of the way together. You’ll part ways again when you feel like it, and that’s exactly what Tom and I are doing. We are planning to take two different routes to Silves. The sun is going down now, and shortly before darkness falls, I spot first the windmill, then the heavy wall of Silves Castle. We reach the first pub where we order drinks and a cheese sandwich, exactly at the onset of darkness. It’s still a good half hour to Residêncial Villa Sodré and Dona Madalena. Here the mobile phone has a signal again, so I can announce our arrival.

But we are stopped once more. I find the first acorn of a „quercus canariensis“ in the last light of the day with Senhor Carlos, a 75-year old farmer on the road just before Silves. His son, he says, planted five trees of this very rare species of oak in front of his dad’s house. These five trees have no problems with their water supply, they can resist the drought, providing shade to the garden. First I spot one acorn on the ground, then another, and yet more on the way in the dust. This species of tree and its acorns are true jewels. Towards the end of the day I enjoy the deep-green trees heaving a deep sigh. Opposite the house, at the neighbour’s as it were the leaves of the orange trees are drying at the moment, and the still unripe green fruit are falling to the ground. Water? Irrigating the citrus fruit was no longer possible as the bore hole yields too little water. In the mountains surrounding the small town the eucalyptus trees line up like soldiers of a large regiment.

But we are stopped once more. I find the first acorn of a „quercus canariensis“ in the last light of the day with Senhor Carlos, a 75-year old farmer on the road just before Silves. His son, he says, planted five trees of this very rare species of oak in front of his dad’s house. These five trees have no problems with their water supply, they can resist the drought, providing shade to the garden. First I spot one acorn on the ground, then another, and yet more on the way in the dust. This species of tree and its acorns are true jewels. Towards the end of the day I enjoy the deep-green trees heaving a deep sigh. Opposite the house, at the neighbour’s as it were the leaves of the orange trees are drying at the moment, and the still unripe green fruit are falling to the ground. Water? Irrigating the citrus fruit was no longer possible as the bore hole yields too little water. In the mountains surrounding the small town the eucalyptus trees line up like soldiers of a large regiment.

In the south of Europe the question of water will soon turn into a question of sheer survival if there isn’t a new way of thinking. Here, bulldozers and caterpillars have terraced the hills to plant the most harmful of all trees. A growing three-year old eucalyptus tree will guzzle up to 60 litres per day and grow straight up towards the sky to a height of six to nine metres. At the moment one ton of wood of this tree felled after nine years will only bring in 16.75 euros. In the olden days, in the heady times before the crises, it was 40 euro. I shake my head. Many people here have probably never learned to read or write in school. What can eucalyptus offer that other trees can’t? Even a freshly planted cherry tree will provide more income after five years than a eucalyptus tree: the same for chestnut, carob and fig trees that are native to here. You can’t have gotten it so thoroughly wrong for hundreds of years, only because an industry is now paying a lot of tax to the state, producing and exporting paper.

I as a foreign observer who’s been watching people’s lives here for over 30 years now and has learned to understand their language, am keener on the slow-growing native trees, the carob, olive, mulberry and fig trees and cork oaks. An umbrella pine grove too is a very beautiful thing, a mixed forest in any case. And very special trees are those oaks with the scientific name „quercus canariensis“… I ask the old man whether I’m allowed to pick up a few acorns. The reply: „Take as many as you want, you’ll need them in Monchique“. So I collect five acorns from each Monchique oak for our forest nursery. The day has a happy ending. The town of Silves and civilisation announce themselves in the shape of a petrol station. Darkness gives way to neon advertising: I buy a bag of potato chips for us, plus a big bottle of water. Then we check in and I am looking forward to our humble dinner.

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia