In 1990, in the city of New York, the heart of capitalism, a group of people came together for one purpose: to ask God to inspire something that would make it possible for the “walls of consumerism” to collapse. These people felt that there was an urgent need to humanise the economy in a decisive manner. The previous year, the Berlin wall, the symbol of communism, had been demolished, and capitalism was able to appear, in the eyes of many, as the triumphant system. And that’s what it was. Its development, through globalisation and the expansion of financial capitalism, increasingly detached from the real economy, made people in many parts of the world hostage to a logic where money seems to be the main – sometimes the only – benchmark.

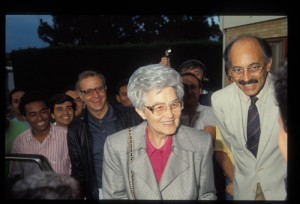

It was the Italian Chiara Lubich, president and founder of the institution known as the Focolare Movement, who took a decisive first step towards this much-needed humanisation, which is becoming more and more urgent.

During a visit to the movement’s headquarters in Brazil in 1991, she saw on the ground the gross social inequalities that characterised Brazilian society. She also realised that the communion of property which was practised among the members of the movement to support the neediest, did not overcome the extreme poverty of many. Nor did it allow others to develop activities of common interest because they were too busy ensuring their own survival.

And then an idea took root: that the movement in Brazil should launch an initiative to set up companies which would make it possible to have a communion of property in a new sense. In this regard, Chiara Lubich said: “I thought that our people (from the movement) could create companies, bringing together everyone’s capacities and resources to produce wealth together for those who needed it most”.

The aim was for these companies to put their profits to common use, hence the name of the initiative “economy of communion”. In concrete terms, it was established that their profits should be equally divided for three purposes: reinvesting in the company, helping the poorest and providing for the movement’s training structures which would disseminate this new culture. This idea spread to many countries, including Portugal.

But other ideas began to emerge: the relationships that these companies establish with their surroundings should break free from the “results at any price” model completely. Chiara Lubich writes that the key is to “institute loyal, respectful relationships, driven by a sincere spirit of service and collaboration vis-à-vis clients, suppliers, the public administration and even competitors”.

Within the company itself, purely functional relationships or those based on exploitation should make way for a spirit of collaboration between everyone so that everything that is done is the fruit of good relationships in the company.

Humanising all the relationships in the economic sphere – this is the grand goal of the Economy of Communion. That is, giving people back the central role that money has stolen and in this way promoting the common good in a different way.

The economy of communion is the guiding principle for hundreds of companies (about 861 worldwide), mainly in Europe and Brazil, but it also inspires many thousands of others. Many of them come together in business hubs of different sizes. In Portugal, there is a small business hub in Abrigada, near Alenquer.

www.edc-online.org (official international website)

www.anpecom.com.br (official website in Brazil)

www.focolares.org.pt/edc (website of the initiative in Portugal)

Note:

From 18th to 20th October 2013, the International Meeting of the Committees of the Economy of Communion will be held in the town of Abrigada near Alenquer.

In the next edition of ECO123, an interview will be published with one of the international figures responsible for the initiative, Professor Luigino Bruni of the University of Florence, Italy.

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia