The economy is in a parlous state. Millions of Europeans are suddenly losing their jobs. Who is giving them any support? The most idiotic view is the one that claims that everything can remain just as it is. Three years ago, in late September, 2017, scientists and politicians gathered together at a world conference at the Portuguese Parliament to debate the possible implementation of an Unconditional Basic Income. Now, faced with the Covid-19 pandemic and the bankruptcy of many companies as the world economy collapses around them, coupled with the threat of an environmental catastrophe and a shortage of our planet Earth’s resources, we need, more than ever before, to develop new and ambitious scenarios for a sustainable future. We’re talking about the very basis for the survival of a world population of almost eight billion people. And that is why the Unconditional Basic Income (UBI) is back on the agenda again. What exactly is UBI? How does it work? How is it financed? Will it be economically viable? And, above all, will it be socially fair? Read the ECO123 report online.

Support a universal basic income

PROSPERITY + FREEDOM?

An essay by Uwe Heitkamp

No strong democracy is based on losers. Digitalisation and automation, the abandonment of coal, oil and gas, the adoption of renewable energy and robot technology are revolutionising our world of work. The world over, they will take more jobs away from many millions of people than they will create. In the car industry, transportation, in farming; almost everywhere: especially after the shutdown of the globalized economy caused on Covid-19. What do we do with those who lose out?

While speculators up there chase virtual money around the planet at several times the speed of light, for financial products that do not exist in real terms for the sake of greedy profits, the globalised economy has opened its doors to new, unknown economic areas. But real life down there looks different, because social inequality is growing with every day. The gulf between poor and rich is getting bigger. If our economies continue plundering the planet on the one hand and degrading people by turning them into the unemployed and receivers of benefits on the other, the coffers of the social state will empty further, unless it finances itself in a completely different way.

Already today, fewer and fewer young taxpayers are paying into a social security fund for more and more old people with longer and longer periods receiving a pension. The pillars of a well-intended social security system are slowly crumbling because demographic development is nowadays completely different to 50 years ago. The coffers of the social state are also becoming empty because many multinational companies such as Apple, Amazon, Google, McDonald’s, Jerónimo Martins and others, and especially the financial industry with stock market speculators and hedge funds, hardly have to pay tax. And so it is time to ask the question, when and how the next financial crash will cause our social state to collapse and whether a government can do anything to prevent that?

Fear. Centuries of fear. It can stop.

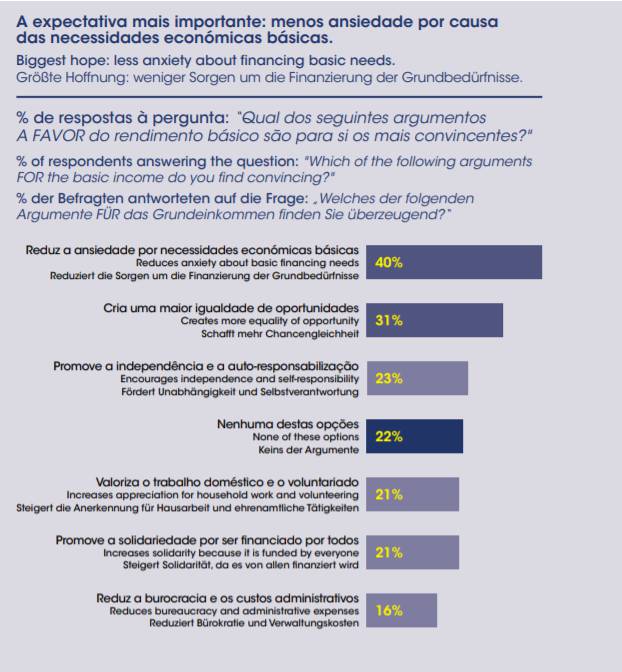

People today are beset by existential fear and the fear of loss, chronic stress, burnout and many other things, and they learn to live with them: with crisis; with longstanding hardship consisting of lacking educational and professional opportunities and life chances generally, an ecological and economic crisis that no longer permits anyone a breather or allows them and their family to have a good time. The 21st century therefore demands a reorganised social state that can withstand present-day and future economic, ecological and social storms.

Many people know what they have got with the old social state of the 20th century. It is natural to mistrust what is new and unknown when one’s very existence is at stake. Perhaps that is one of the reasons why the idea and the concept of the UNCONDITIONAL BASIC INCOME (UBI) is still relatively unknown in Portugal. But what could this new social state of the 21st century look like, ECO123 asks the experts?

Money for all. From the State, with nothing in return. Just like that?

The world of work in the last century was different to the one we have today. Many employers and employees once strove for stable, lifelong, full employment as the norm. Economic growth and big profits were the unreserved goal of every government in the old post-war Europe. People who lost their jobs or fell ill or reached retirement age could apply for unemployment benefit, took advantage of a range of benefits from the state health service or applied for their state pension at the legally defined age. But the reason this definition has increasingly shifted in the new century to the detriment of those covered by social insurance is that the social insurance system was built on pillars that no longer support it today. Portugal, which did not begin to adopt the achievements of the European social state until 1986, built up its own social insurance system following the French model.

It is a long time since there has been full employment, and economic growth has mainly existed in industries that save on labour through automation. As globalisation began, many traditional businesses were closed. Their machines moved away to Asia. But those employers and employees who stayed behind and paid social security contributions for decades realised at the start of this new century that the social state was gradually running out of money, the benefits were being cut more and more, and retirement age was being postponed.

Demographic changes mean that today increasing numbers of people are drawing a pension for longer and longer, which has to be raised from fewer and fewer young employees through their contributions. Originally, the opposite was the plan. The solution to the problem: Cosmetic repairs. Here the contribution rates were raised, there the benefits were cut, the pension age increased, public holidays cancelled and reinstated. Neither the Ministry of Labour nor the Ministry of Finance have so far succeeded in bringing in enough tax to keep a balance between budgets and contributions for healthy social insurance. The additional effect of the heavy exodus of young, qualified employees of working age on the funding of pensions exacerbates the consequences for our social security system. The following suggestions have been floating around in political discussions:

1. a further reduction in the level of pensions; or

2. an increase in the contributions for pension insurance; or

3. a significantly longer working life; or

4. more immigration of young foreigners; or

5. the simultaneous adoption of all the above measures.

None of the five options is easy. Each one meets resistance: from the unions, businesspeople, opposition parties, depending on who is in power at the time. It will soon become clear that you shouldn’t be too hopeful as regards the different courses of action. Although some improvements have been made under António Costa’s socialist minority government, these are only minimal corrections in a complicated, expensive, inefficient and unfortunately only reactive social state, which – to express it in numerical terms – had to take care of 3,5 million recipients of subsidies every year.

New times demand new solutions.

The European social state of the last century was based on a traditional understanding of the family. But in the course of two generations, real life has departed from this model. People today live more individual lives. In Portugal, almost as many women (70.2%) work as men (77.1%) in the 15 to 64 age range and seven out of ten marriages end in divorce. But our social security system continues to work in accordance with the old models of the last century.

To what extent are the pillars of our social state crumbling? ECO123 asked former Minister of Labour and Social Security José António Vieira da Silva in an interview.

Digitalisation and the automation that goes hand in hand with it are radically changing everyday life and the world of work. They will make a change of outlook and a paradigm shift unavoidable. If more and more robots replace people, work will play a new role. The future GDP (Gross Domestic Product = the total value of all the goods and services produced by an economy) will be generated with fewer working hours and more machine time. What are people needed for then?

Of course, a majority of the workforce and their union representatives see the increased use of automata and robots as a threat. In the Tesla car factories, human labour is already the exception. Robots fit windscreens and wheels, lift chassis from one platform to another, from one production line to the next. At Volkswagen and General Motors, there are still some 100,000 workers screwing cars together, but with Tesla in Fremont, California, there are only 3,000 technicians and controllers of 160 autonomously working robots, and rising. Anyone who doubts what everyday work will soon look like the world over in the car factory of tomorrow should visit https://www.youtube/watch?v=8_1fxP15ObM.

How does the Unconditional Basic Income work?

That the digitalisation and automation of the world of work represent a historic opportunity to completely reorientate ourselves is something that only a few people have discovered. If people are firstly complemented and later replaced by machines of all kinds and by automata with artificial intelligence, opportunities arise for reorientation, for example on the basis of the Unconditional Basic Income.

This is how it could work:

- The state transfers a payment equivalent to the minimum salary, which is based on the subsistence minimum, to all citizens throughout their lives and month by month, funded out of the general budget through taxation. To fund this, the following simple correlation applies: high basic income needs high taxes, a low basic income makes it possible to have low rates of tax.

- The basic income is paid with no conditions, with nothing in return, without an application and therefore with no bureaucratic workload, as a universal transfer to everyone of the same amount. Of course it is possible – if politically desirable – for a lower sum to be paid for children, if politicians and the general public are of the view that children living in a family household have lower daily costs than adults.

- There is no longer a difference between the employed and the unemployed; equally, no distinction is drawn between independent and dependent employment.

- In the basic income system, all Portuguese citizens will be included from birth until the end of their lives. Portuguese citizens living abroad lose their entitlement.

- Foreigners coming to live in Portugal do not receive the full basic income immediately, but only after a longer waiting period and gradually, depending on the legal length of stay in Portugal. This prevents abuse.

- Everyone receives the basic income tax free. Additional income of all kinds (in other words all investment income such as interest, dividends and distributed profits as well as rent, bonuses and royalties) is assessed at source and taxed from the first to last euro at a single rate of tax that applies to all income. Taxation at source enables all distributed profits to be assessed as the tax base, i.e. including those that are paid to owners and companies based abroad.

- There are no tax-free amounts because the basic income is already a tax-free amount. Professional expenses must be claimed directly from the employer. Neither the state nor the tax department are involved. They are treated as expenses and are not tax deductible.

- The basic income replaces all social security benefits paid for through tax and contributions: there is no statutory pension or unemployment insurance, nor unemployment benefit, social assistance, housing or child benefit. Social security is abolished.

- Continued payment of salary in the event of illness, holiday pay and similar commitments agreed by the parties or the contractual rules are not affected by the basic income. They remain in place.

- For health and accident insurance, there are three options: either an obligation to have basic insurance, with the necessary amount for basic insurance being part of the subsistence minimum (minimum salary plus lump-sum for health insurance), which would thus be included when the basic income is set by politicians; the unconditional basic income would therefore have to be increased accordingly; or the state gives every citizen state insurance vouchers that can be redeemed at every health and accident insurance company. Then, for basic insurance, there would have to be a prohibition of discrimination (no one may be excluded) and an obligation to issue contracts (everyone has the right to a contract). Or the basic income is complemented by a state health system, whereby basic medical care – however extensive – is offered to everyone free of charge.

Does the UBI make socio-economic sense?

One fundamental strength of the concept of the unconditionally guaranteed basic income is the transparency and simplicity of the procedure. The UBI is a tax system that can be explained to a primary school child. As there is only one single and unchanging gross tax rate on all types of income, tax payments can be made directly to the tax department at source, where they arise. No tax return is needed. Bureaucratic investigation and control procedures for checking whether state assistance is being used correctly are just as unnecessary. The UBI is not linked to any pre-conditions. No one checks whether there are good or bad reasons for support. No one ties state assistance to specific pre-conditions. No one goes without assistance and no one falls below the minimum for subsistence.

The unconditional basic income is geared to the current reality of life in the 21st century, and to that expected in the future. It is the answer to the socio-political challenges in the modern social state brought about by demographic ageing, individualisation, digitalisation and a change in work ethos. The UBI takes people as they are, without wanting to force them into a norm. It is for that reason that the basic income is called unconditional.

The modern social state in the 21st century has to be strong, and work in a way that is just, fair, sustainable, efficient, transparent, simple and shows solidarity. It must be resilient enough to withstand a future financial crisis unharmed. It must deal with problems preventively and not try to solve problems by reacting in retrospect. The introduction of the unconditional basic income (UBI) would offer a unique chance to link the funding of the UBI with tax reforms, under which state structures would also be streamlined.

500 euros for everyone? Every month. Throughout their lives.

Just imagine that everyone had a sum of between 500 and 600 euros transferred punctually to their bank account every month by the tax department. First of all, everyone would receive money from the state that, from the state’s point of view, would correspond to a reimbursement, and hence the opposite of a tax payment. The UBI would thus equate to a negative income tax. In this way, the state could explain to its citizens why they pay taxes. The tax department in Portugal would acquire a positive narrative. A social state can only pay its citizens a universal basic income if each taxpayer is certain firstly that each individual really would pay tax and secondly that the tax they pay would be properly invested. Everyone who earns an income, even the owners of robots, the financial sector and multinational companies should pay 50 cents tax at source on every euro they earn. But what is essential is that the government taxes investment income in the same way as income from employment.

The Unconditional Basic Income (UBI) is the radical new beginning of the modern social state in the 21st century. But it is not a leap in the dark with no safety net. The UBI follows a simple logic. It avoids the complicated, untransparent maze of taxes and deductions from employment income, social security payments and socio-political subsidies that is administered by an inflated bureaucracy known as “Segurança Social”. It simply requires a 50% tax on every euro earned. In this concept, the following principle applies: those who earn more pay more tax than those who earn less.

The Universal Basic Income (UBI) provides people with security and a firm foundation and it creates room for manoeuvre. If people’s material existence is guaranteed in all cases and at all times, they are freed from worry about economic survival. The UBI also creates the conditions that can be used by people for independent activities. Those who want to are only obliged to do the work that they enjoy and is meaningful to them, and which they are capable of doing. “Mindless, degrading tasks can be done by robots – around the clock, better, more reliably, more tenaciously and more cheaply that they could ever be done by humans,” scientists argue. People for whom the UBI is insufficient or who do not want to give up their professions just keep working as before. And people who want to move into work from unemployment are not punished by the loss of social benefits. They are rewarded from the first additional euro they earn onwards.

How much Welfare State do we want (or are we able) to afford?

The question of whether the basic income can be financed will in the end be the question that decides everything. What makes it even more critical is that the question is formulated in completely the wrong way. Because of course the unconditional basic income can be financed if people want to finance it. The question is no different at all from the question of whether today’s and tomorrow’s pensions are still secure. Of course they are, or maybe not? However, the question that is much more important is how high they will be and who will pay for them. It is exactly the same with the basic income.

The simple calculation is: the higher or lower the UBI is set, the more expensive or cheaper it will be to fund out of the national budget and the more difficult or easier it will be to implement. A high (or low) unconditional basic income requires high (or low) direct taxation rates, which reduce individuals’ performance incentives significantly (or not at all).” The question about how expensive our social state can be needs to be discussed.

The idea of having 500 or 600 Euros or even more for everyone, every month, without being tied to conditions, is not new but it is still revolutionary. Of course the question about the level and the amount of the subsistence minimum is a politically highly controversial topic. Nonetheless, the question “why do we wear people out through work, if alternatives using machines and automata are available?” is relevant. For an economy to prosper it is important to be innovative, creative and competitive. If the UBI was capable of commanding a majority politically, any degree of financing and redistribution from those earning more to those earning less could be put into practice. Politicians would be free to determine the level of the basic income and the income tax rates. A modern social state must be geared towards those who wish to achieve something, and not towards those who are reluctant to do so. Its aim should be to empower those who wish to do something positive. And it shouldn’t employ huge bureaucratic effort to force reluctant individuals to perform tasks than can be carried out better and cheaper by robots. People who know that the minimum they need to survive is assured, whatever happens, will see the forthcoming challenges such as climate change not as a threat but as an opportunity. Because only those who feel that their very existence is secure are really free to act independently in order to lead a dignified life. In this way, the unconditional basic income also becomes a socio-political tool for sustainable, ecological action. A strong democracy is based on winners.

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia

Eco123 Revista da Economia e Ecologia